Russian President Vladimir Putin must be finding it hard to contain a wry smile as the European Union struggles with Greece's debt problems.

Events are playing into his hands by diverting attention from the conflict in Ukraine and offering him a chance to exploit differences in the EU which might undermine unity on sanctions against Russia over Ukraine.

Russia's fragile economy would certainly not escape unscathed if Greece left the euro zone or the EU, and the crisis could serve as a worrying lesson for Moscow as it builds its own political and economic bloc with other former Soviet republics.

But Russia is now one of the few countries Athens might realistically turn to for money and state-run media are having a field day, depicting the EU as a discredited and dysfunctional empire in terminal decline.

"I do think that they're going to use Greece as a tool against Germany, as a tool against the European Union," Yevgenia Albats, a prominent Russian commentator and editor of the independent New Times magazine, told Reuters.

"That's exactly what the Soviets did, that's exactly what the KGB did during the Cold War, when they were using countries and governments, especially poor ones, in their war with Western civilization."

State media portray Greece's crisis as just the start of the EU's problems, suggesting Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy could be next if Greece left the euro zone.

"Grexit", many loyal media outlets suggest, is now all but inevitable.

News about the crisis on state-controlled news channel Russia-24 is accompanied by a graphic declaring: "Greece — almost over." The popular daily Komsomolskaya Pravda this week ran the headline: "Greek tragedy. Divorce already near."

Far-left politician Eduard Limonov wrote an article for Izvestia newspaper under the headline "Crumbling empire" that smacked of a feeling of revenge, nearly a quarter of a century after the Soviet Union fell apart.

"In short, many countries have reasons to leave the EU but Greece will be the first to summon up the courage to do so," he wrote. "Everything is bad, everything is heading towards the European empire falling apart..."

Reassuring the People

The Kremlin has played down suggestions Russia might bail out its Orthodox Christian brothers, describing it as a problem for Athens and its creditors to solve, "not a matter for us."

With a hint of schadenfreude, the Kremlin voiced concern about "negative consequences" for the EU and the central bank and the Finance Ministry offered reassurances that the Russian economy and financial markets would not be badly affected.

Russia has relatively little exposure to Greek banks and government debt, but a Greek exit from the eurozone would limit risk appetite worldwide and Russian assets are seen as risky.

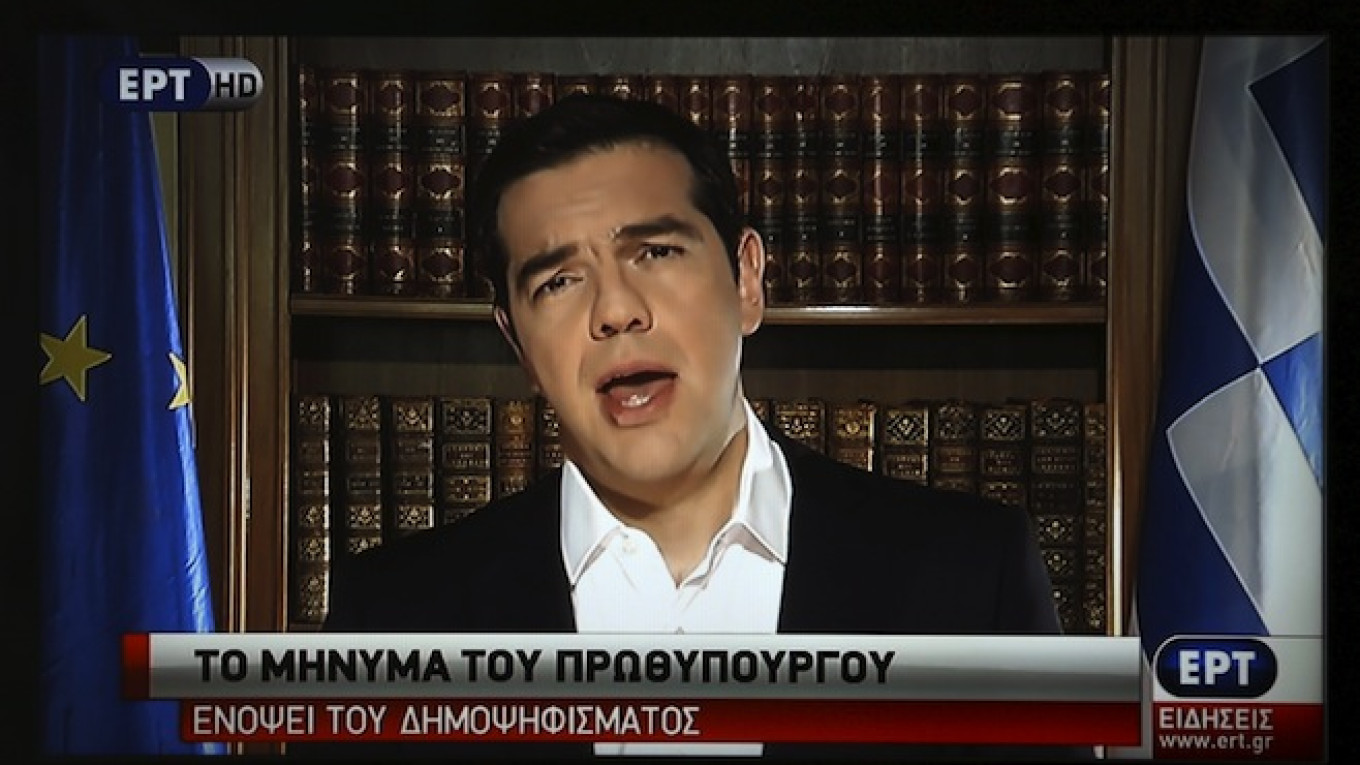

Few would rule out entirely the possibility that Putin is still waiting for the best moment to come to Greece's rescue, or that Prime Minister Alexei Tsipras might make a last-minute request for aid after making two visits to Russia this year.

Washington has been lobbying European leaders to do all they can to support Greece; global markets would be disrupted if Athens left the euro and Greece could block an extension of EU sanctions against Russia or make NATO decision-making difficult if it felt it had little to lose.

Some Russian experts want Greece to give up on its Western partners, join a Russia-led customs union and sign up for the Moscow-dominated Eurasian Economic Union, intended to challenge the economic power of the EU, China and the United States.

"It has one option; leave NATO and then, for company, join us," said Mikhail Delyagin, a prominent economist.

But Russia's embrace of Greece has so far been less than fulsome. Both sides said financial aid was not discussed when Tsipras and Putin met in St Petersburg last month, where the main outcome was the signing of a memorandum of understanding on cooperation over building a gas pipeline.

"There are no resources (in our budget to provide money)," Deputy Finance Minister Sergei Storchak told Reuters at the time.

Russia has its own economic crisis, worsened by the EU and U.S. sanctions over Ukraine and a fall in the global price of oil, its most important export. Bailing out another country might anger voters facing financial problems themselves.

Moscow did not bail out Cyprus when it faced a debt crisis in 2013 and a $3-billion loan to Kiev in December 2013, intended as a sweetener to prevent Ukraine joining mainstream Europe, backfired when President Viktor Yanukovych was toppled two months later following street protests.

Russia has other reasons for caution. Holding together a large political bloc is not proving easy for Brussels and may not be for Moscow if its Eurasian Economic Union expands beyond Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan.

Russia is already struggling to convince others to adopt one currency.

Some experts say the EU's problems could also cause the United States to lose faith in Brussels as an economic, security and political partner, encouraging it to play a more direct role in Europe, something Moscow would oppose.

"All this strengthens the tendency towards a return to the standoff of 30 years ago, possibly in the worst form," foreign policy analyst Fyodor Lyukanov wrote in the government newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta.

In other words, Putin might yet not have the last laugh.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.