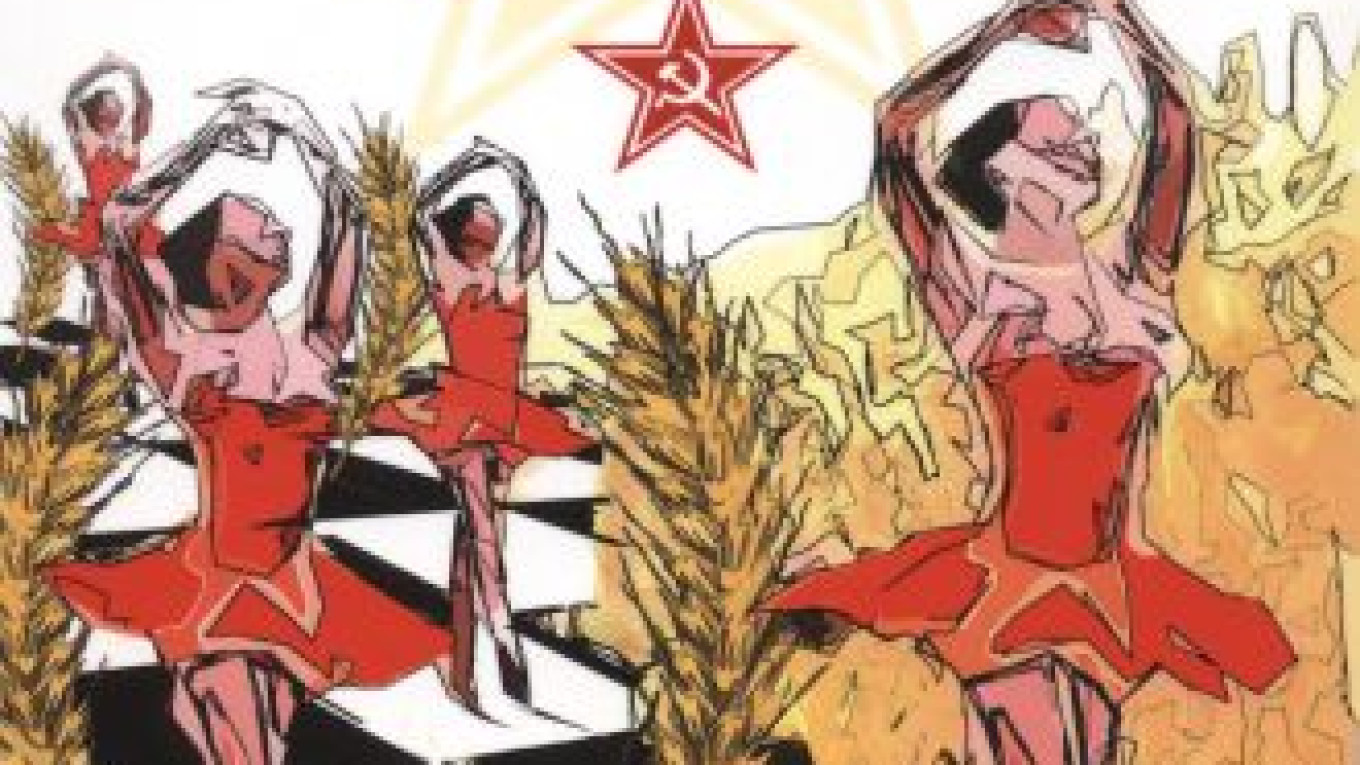

The title of John Miller’s new book, “All Them Cornfields and Ballet in the Evening,” is a fitting illustration of the fact that, until recently, Russia was (and perhaps remains) another planet. In the classic British trade-union satire “I’m All Right, Jack,” Peter Sellers, playing a tragicomic, radical trade unionist, imagines the Soviet Union as a worker’s paradise. Asked whether he’s ever been to Russia, he replies wistfully that he hasn’t: “I’ve always wanted to though … all them cornfields and ballet in the evening.”

As Miller makes clear in this excellent memoir of decades spent in the Soviet Union, it’s easy to forget how far Western impressions of Soviet Russia differed from the grim and, at times, bizarre reality. Foreigners visiting Russia for the first time in the early 1990s, seeing the organizational decay and general dilapidation of the country, could be seen scratching their heads and wondering how the CIA and its counterparts had managed to keep the West petrified about the Soviet threat for so long. In the Internet and post-Kurnikova, post-Sharapova age, it’s also easy to forget that not so long ago, the dominant images of Russian women were not lithe, long-legged blonde beauties. Instead, harrowing images of hairy, muscled creatures pumped up on anabolic steroids, occasionally glimpsed putting the shot or hurling javelins at the Olympic Games would spring to mind. For many years, it was the first manned spaceflight — piloted by the heroic Yury Gagarin — that symbolized the awesome and largely imagined achievements of Soviet industry and technology to the West, rather than the make-do, botched and backward reality of daily life in Russia.

As a foreign correspondent in the U.S.S.R. for more than 40 years — predominantly in Moscow and with the Reuters news agency — Miller was perfectly placed to chronicle this discrepancy, and his idiosyncratic reminiscences of life in the Russian capital and the key political figures of the day, all delivered in a brisk, cheerful, no-nonsense style, make for an engaging read.

Miller began his reporting career in Moscow during the reign of Nikita Khrushchev (“a wonderful old windbag”), and his journalistic eye and ear for juicy gossip soon had him giving eyewitness reports of gems such as the paunchy Soviet leader’s very diplomatic quip to a high-powered delegation from Paris: “Our women do work, and they do honest work. Not like women in France who, I’m told, are all whores.”

Delightful snippets such as this come thick and fast. There is his description of Khrushchev’s anti-alcoholism campaign, undertaken to safeguard Russia’s image in the eyes of foreign tourists as the country opened during the post-Stalin Thaw, with police officers being sent out across Moscow in squadrons of motorbikes, strapping the inebriated into their sidecars and hauling them off the streets. His description of the pained, protracted and entirely illogical dealings with Soviet censors is worthy of Kafka, as are the misfortunes of committed Western socialists and Communists who moved to the Soviet Union in search of an ideological paradise. As they quickly discovered — some in labor camps — it was very far from being a promised land of endless cornfields and ballet in the evening.

In the latter category, Miller’s meetings with Cambridge spies Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess and Kim Philby are rich in firsthand, powerful observations of telling details. Although Miller himself, in his typically blunt style, questions their importance in the grand scheme of things (“Who cares that a couple of often drunken diplomats took up with Uncle Joe and flogged a few secrets to his police force?”), he readily admits that at the time “it was a hell of a ‘Story,’ part and parcel of the Cold War, material for a thousand thrillers.”

Miller clearly has little sympathy for these men, regarding them as misguided traitors, but there is a grim poignancy in his description of Philby’s personal betrayal of Maclean (he ran off with his wife) and Burgess’s shady demise: “Burgess, offered male lovers, said he preferred to find his own. But on his first expedition, he was badly beaten up and lost most of his teeth. His hosts [the security services] found his experience amusing but had dentures made and fitted for him. Unfortunately, they were so stained and uneven that Burgess hated them for the rest of his days.”

Miller’s account of meetings with Burgess, his perpetual cadging of drinks and his general seediness, segues nicely into another of this book’s great strengths — its description of the life of expats, predominantly journalists and diplomats, in Moscow. “At the end, Burgess was probably the loneliest man in the Soviet Union,” Miller tells us. “He didn’t like Russians, because they couldn’t talk about the Reform Club and the bars of London. His friends could be counted on one hand, and some of them were British correspondents.” That’s how low he’d sunk.

Miller, clearly not one to pull his punches, gives some wonderfully juicy character sketches of notable figures in the hack pack of journalists that lived on “Sad Sam” (“Sadovaya-Samotyochnaya Ulitsa, a ghetto for Westerners”), and is particularly unsparing in his treatment of British diplomats.

Former British ambassador Sir Geoffrey Harrison got off on the wrong foot with Miller when he barred journalists from using the embassy shop, where they had been able to stock up on cornflakes, toilet paper and other items that were hard to come by in Soviet Russia. The duty-free Scotch was particularly sorely missed.

Miller is clearly somebody you should avoid getting on the wrong side of, and Russia’s current crop of British diplomats would do well to read this book and learn one golden rule: Beware the wrath of British journalists, especially if you have deprived them of their kippers and duty-free Scotch. Miller takes wicked delight in informing us that Sir Geoffrey (“tall, suave, chinless”) later confessed to his Foreign Office masters that he had fallen for a classic KGB honey trap and had been having an affair with his embassy maid, a KGB agent. They had even been photographed making love in the residence’s laundry. Although the matter was hushed up, only coming out years later, he returned to England in disgrace.

In his general outlook and comments on Russia and Russians, Miller avoids any romantic idealization of the country’s soul, soil or citizens, but also avoids plunging into the resigned pessimism that overcomes many in the expat community here. “They [the Russians] have done some dreadful things to each other and to others,” he concludes, “and I fear they will behave badly again … Putin’s Russia lacks any ideology except a crude notion of capitalism. But I am convinced that the day is coming when Russia will be an ordinary, normal and — heaven forbid — boring country.” Some will agree with the diagnosis here and elsewhere in the book, without being entirely convinced of the prognosis.

The book is not without its faults. Firstly, compressing 40 years’ experience into just over 300 pages in a fairly impressionistic style and with almost no reference to dates can lead to confusion, with lines between the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s frequently blurring.

Secondly, although the book provides informed insights into spies and spying, being liberally littered with references to these dark arts, you can’t help wondering if Miller is being entirely candid when he says he was in no way linked to the British secret services during his time in Russia, even turning down a job offer when approached by them. Taught Russian by the British military and having served in MI10 (the intelligence branch dealing with Soviet military equipment), the son of an intelligence officer in the Royal Air Force, he would have been an ideal candidate, and it’s hard to imagine that he entirely slipped through the net.

Another complaint is the plethora of typos, grammatical errors and spelling mistakes, for which the book’s proofreaders should be given a good spanking — very much in the spirit of Miller’s book, I can tell you that there’s one member of the current diplomatic community in Petersburg who would particularly relish this task.

These, however, are all minor quibbles that actually add yet more character and color to a book that is already packed with rich and distinctive impressions. Miller was here for more than 40 years as a professional observer, and reading his excellent memoir you can’t help feeling that it was time well spent.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.