“See, I turn everything upside down. That’s how I do it,” the director told me during a break in rehearsals.

“That’s not how Sam Shepard does it,” the man went on. “Shepard likes good Irish acting. He likes actors playing the text.”

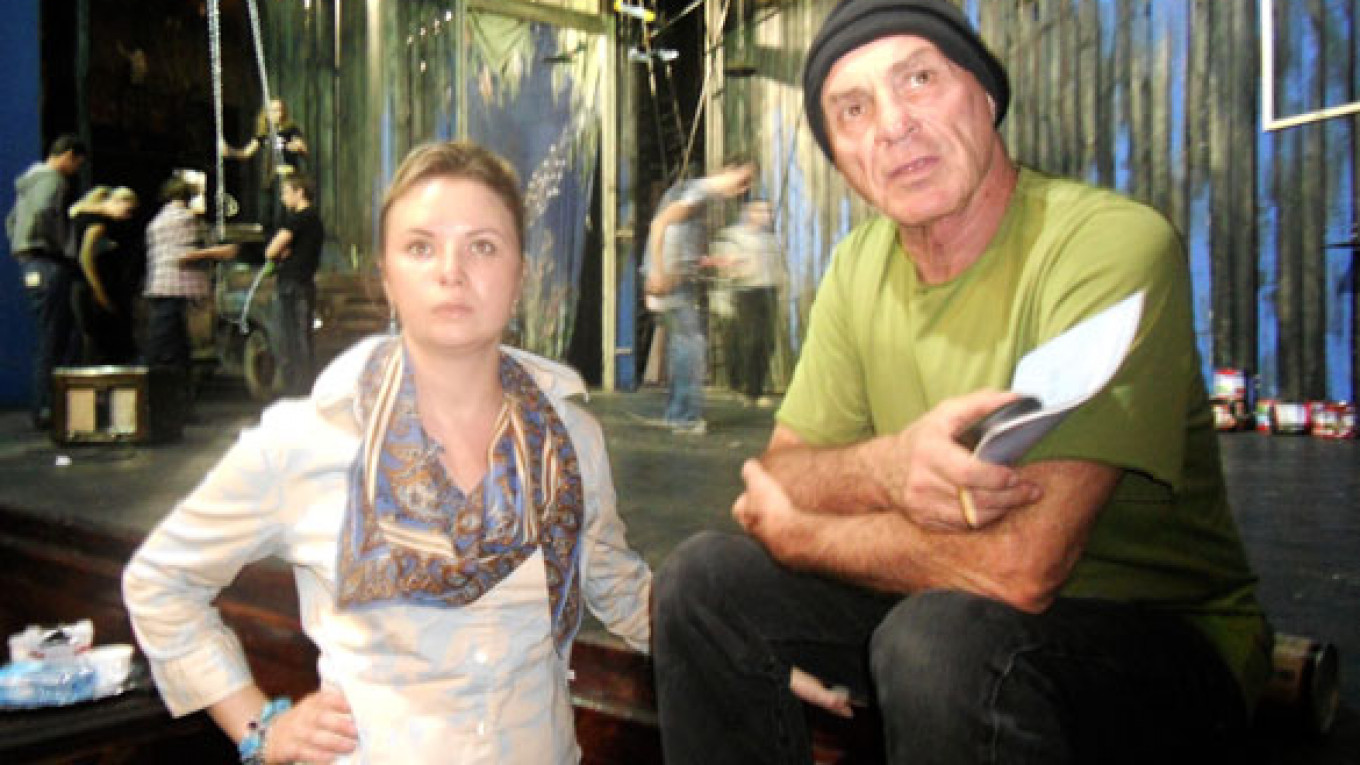

Just three days before this conversation took place I had no idea I would be sitting in a theater in Saratov, talking to the renowned American director Lee Breuer.

My schedule said I was to get on a plane in mid-October to fly down to see the premiere of Breuer’s production of Shepard’s “The Curse of the Starving Class” at the Saratov Theater Yunogo Zritelya. Fate, however, had something else in store for me.

Valery Raikov, the theater’s managing director, called me last week and asked if I could make a quick advance trip. Breuer, who does not speak Russian and is making his Russian directing debut in Saratov, wanted to get an outside opinion. Rehearsals, which began at the end of August, were going well, but questions were cropping up, too.

Breuer is no stranger to Russia.

“The Gospel at Colonus,” one of the landmarks of recent American theater and now running in its 30th year, played Moscow during the Theater Olympics in 2001.

Last year Breuer’s unorthodox, award-winning take on Henrik Ibsen’s “The Dollhouse” was a featured entry in the Stanislavsky Season theater festival.

Both of those shows were produced by Mabou Mines, a New York company that Breuer helped found.

All of that was buried deep in my memory by the time I arrived at the theater from the airport last week. Rehearsals were under way. Breuer sat far to the right. in about the 10th row, and a few other people were scattered around the house. An actor was preparing to launch into a scene — what turned out to be a rousing, five-minute, 40-second lip-synch rendition of Al Green belting out an astonishing live performance of the famous Sam Cooke song, “Change is Gonna Come.”

“What is this?” I thought.

It has been a while since I have seen “Curse” performed, but I didn’t remember Al Green in there.

That’s Lee Breuer, though, finding in plays what we had no idea existed.

“I want you working on your moonwalks!” Breuer told the actor through a translator. “This has to be like a rock concert on MTV!”

Breuer was all over the camera man, who was shooting the scene from behind the stage so that it was simultaneously projected on a wooden screen. The trick is that we see the actor coming and going, front and back. When his back is turned to us, we see a close-up of his face on the screen. When he’s facing us, we see him wiggling his butt at the camera.

“The camera can’t be static!” Breuer barked at the unseen man backstage. “You’ve got to follow his every move. We’ve got to see him when he’s on the ground. We’ve got to see him spinning around.”

The cameraman, responding by way of the stage manager, whose words were translated into English for the director, objected that the hole in the wall, through which he was filming, was too small to allow for that kind of movement.

“Then make the hole bigger! Make it as big as you need!” Breuer shouted energetically. “I need that camera moving! If you can’t do that, it’s boring! And I’ll have to cut the song!”

They ran through the scene again, and it was like someone had poured gasoline on it and tossed in a match. What five minutes before had been a simple musical number was now an incendiary, emotional blast that came crashing down on those of us sitting in the hall.

I was exhausted when the scene came to an end. “What an ending that’s going to be,” I thought. At least until Breuer came over to chat for a short moment.

“That’s the first scene,” he said. “What do you think?”

I laughed to myself and thought what I often think when I see a production by Lee Breuer: “I sure didn’t expect that!”

Over the course of three more days there were plenty more surprises.

Like seeing the young woman from the dysfunctional family Shepard is exploring suddenly rise up and do a dance on a sparkling chain in mid-air during a dream scene. Or seeing the same character fly, topsy-turvy in slow motion, across the stage, blown to smithereens by an explosion that two-bit bandits had meant for her father.

Or seeing both the girl and her brother turn into zombies stalking the stage as if they were escapees from “Night of the Living Dead.” Or seeing a sleazy attorney waltz onto the stage for the first time — a dead ringer for Elvis Presley, replete with sweeping hairdo and immaculate white jacket.

For the moment Al Green has been pushed aside, and now it’s the velvety, Las-Vegas-tinged voice of Elvis pulsating from the speakers. “It’s now or never / Come hold me tight / Kiss me darling / Be mine tonight…”

“How’s Elvis look?” Breuer asked me later. “Does that work?”

Did that work? Was Elvis king?

Breuer would have been better off asking me about the scene where Elvis leads a stage full of losers, drunks and thugs in a butt-wiggling dance as they exchange threats.

Actually, best he didn’t. By that time I was laughing too hard.

Lee Breuer’s production of Sam Shepard’s “The Curse of the Starving Class” plays at the Saratov Theater Yunogo Zritelya on Oct. 12 and 16 at 6 p.m. Tel. 7 (845) 226-1541.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.