TROITSK — When Anatoly Pakhomov relocated from Eastern Siberia several years ago to be closer to his daughter and grandchildren in Moscow, he chose this city of 39,000 people in the Moscow region rather than the capital.

"It's quieter here," he said as he waited for a local bus at a beat-up though well-swept bus shelter on a main road. Dirt paths disappeared into the thick woods across the street. "Birds in the woods sing at night," he said with a smile.

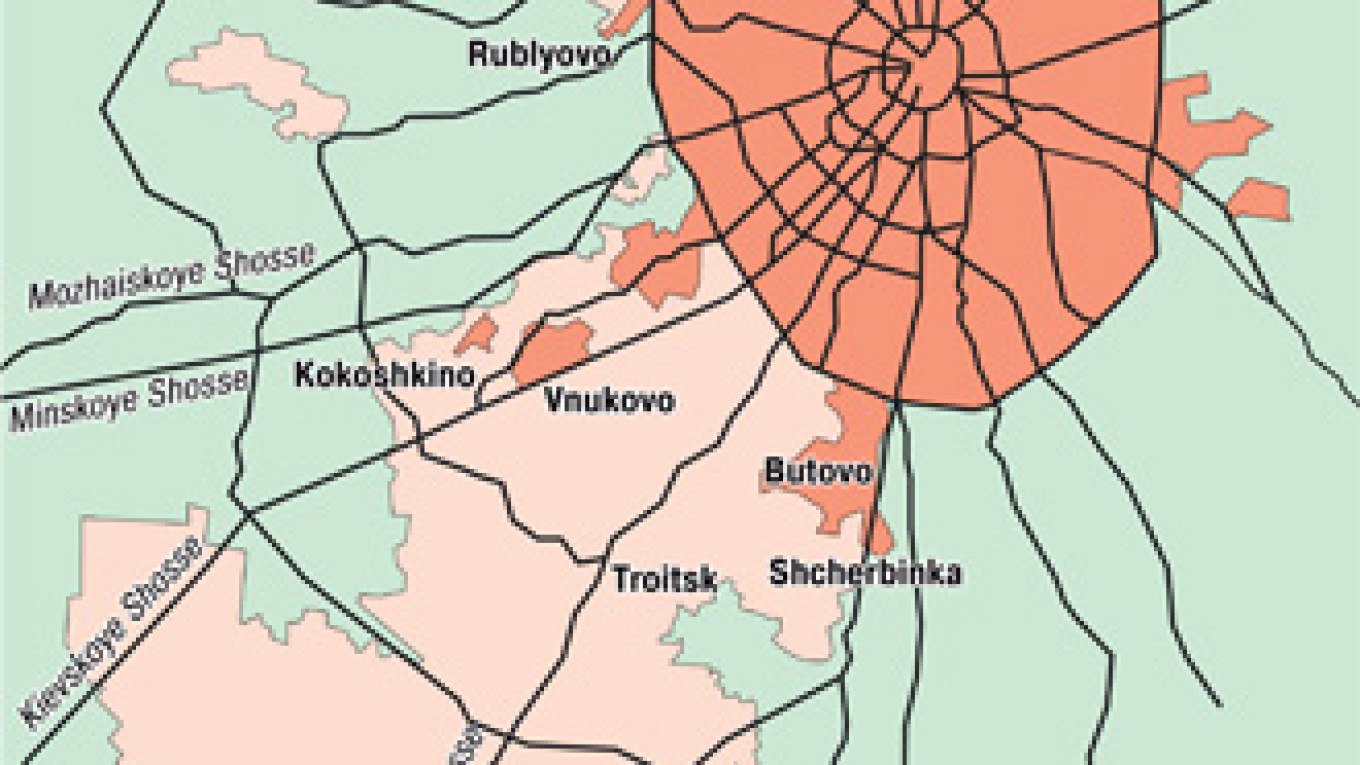

On Sunday, this low-key city about 20 kilometers southwest of Moscow, along with another small city and three sprawling municipal districts, will officially become part of the capital under the federal government plan to stretch Moscow's borders.

On July 1, hundreds of thousands of Moscow region residents will turn into moskvichi, or residents of the capital proper. All of them will need new registration stamps in their domestic passports, while many of them will receive new social benefit cards, file tax documents to different tax offices and tackle other bureaucratic changes. Meanwhile, both city and federal officials have promised to bring more investment and jobs to the new sections of Moscow, while retaining and even increasing social welfare benefits for the one-time regional residents.

Like many people here, Pakhomov sees pluses to the capital's expansion but worries about changes proposed by former President Dmitry Medvedev and other top officials to develop the area's land. The suggestions, aimed at reducing Moscow's congested traffic and increasing its attractiveness to foreign investors, include relocating federal ministries to the added territory and building a global financial hub there from scratch.

At first mention of the expansion, Pakhomov, a 61-year-old retired railroad worker, said "the most important" effect for him will be the increase in his pension from 8,000 rubles ($240) per month to the Moscow pension minimum of 12,000 rubles a month.

But a few minutes later, he said the government "shouldn't mess with the woods," where children play and adults enjoy summer sports. He said wryly that "we have a lot of investors."

His expectations aren't far off the mark.

Social benefits will be preserved and even increased for current residents, said the head of Moscow's Department of Social Protection, Vladimir Petrosyan. He told a press conference on Monday that if a newly added resident has a pension below the Moscow minimum of 12,000 rubles, the person will receive an additional payment to bring it to the Moscow level.

In addition, any benefits that Moscow region residents receive as of June 30 will continue to be paid, even if they exceed those given by Moscow or if Moscow doesn't offer such a benefit, Petrosyan said.

In addition, people in the added areas who hold social benefit cards, which provide pensioners and disabled people with benefits such as welfare payments and discounts at pharmacies, will receive Moscow cards. Petrosyan warned that the Moscow region cards will stop working on July 1. He said, however, that the department's offices in the new areas will stay open on Saturday and Sunday.

The funds for these social programs have been transferred from the Moscow regional budget to the capital's coffers, Petrosyan said, according to a of the press conference on the department's website. For welfare benefits and social services alone, the amount of money required for the new residents of Moscow is about 3 billion rubles ($91 million), he said.

By contrast, registration with the local branch of the Federal Migration Service, which is required for everyone living in Russia, can be dealt with as people find the time, said Fyodor Karpovets, chief of the service's Moscow division.

"You don't need to run for a Moscow stamp today, because all of the social services are already in the loop and will work with the actual documents already in the hands of residents of the annexed areas," he said, Interfax reported.

Transferred to Moscow will be the small cities of Troitsk and Shcherbinka and the Naro-Fominsk, Podolsk and Leninsky municipal districts, according to Moscow's official website on the new borders.

Currently a city of 107,000 hectares, 148,000 hectares from the region for a total of 255,000 hectares, an increase of nearly 2 1/2. The southwest section of the city will now stretch all the way to the Kaluga region.

In an interview with Vedomosti last summer, Moscow's deputy mayor for economic policy, Andrei Sharonov, said expanding the city to the southwest would make sense.

"If you look at what surrounds the capital, it is overcrowded to the north, east and west of the capital," Sharonov said in the interview.

He acknowledged that there is an obstacle to incorporating the southwestern land, at least from a development point of view. "The flipside is an absence of infrastructure there: no roads or power," he said.

That has regional residents hopeful that the influx of investment will bring jobs, as many Moscow region dwellers commute for hours each day in long traffic jams to jobs in the capital. What's more, people are hoping that the enlargement will bring state medical clinics and hospitals, which are few despite the large population of the areas being added.

Taxation will be the source of funding for these programs. The rate for personal income tax won't be affected, since that rate doesn't depend on a person's region of residence but rather is set at the federal level, with a rate of 13 percent for all residents of Russia.

Svetlana Zobnina, a director at the Moscow office of Ernst & Young, said rates for transport, land and property taxes could change, however, since those are set by regional authorities.

On Tuesday, physicists Natalya, 61, and her husband, Sergei, 64, were out for a stroll in Troitsk, which has been a naukograd, or science city, since thousands of scientists relocated there at the Soviet state's behest decades ago. The couple has heard of many government promises for their small city post-expansion: more jobs, bigger pensions, higher salaries at scientific institutes, cheaper transportation to Moscow, more hospitals.

"I'm very skeptical," Sergei said, declining to give their last names.

Natalya was a bit optimistic. "We have a saying, 'Live and see,'" she said.

Authorities could entrust construction in Greater Moscow to a specially created state company, which would be at least 25 percent owned by the state.

A source told Kommersant that Finance Ministry officials are behind the plan and they have already presented plans to First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov.

According to the Finance Ministry plans, the Russian state and Moscow city government would found the company, controlling a share of between 25 percent and 50 percent.

Should outside investors join the project, it will likely receive loans from state banking giants Sberbank, VTB and Vneshekonombank under a state guarantee, the source said.

Government officials put the cost of incorporating 150,000 hectares of Moscow region land into the capital and creating a global financial center and a new home for parts of the federal government at 419 billion rubles ($12.7 billion).

On July 9, the plans will be handed over to Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, who initiated the project while president, the newspaper reported Thursday.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.