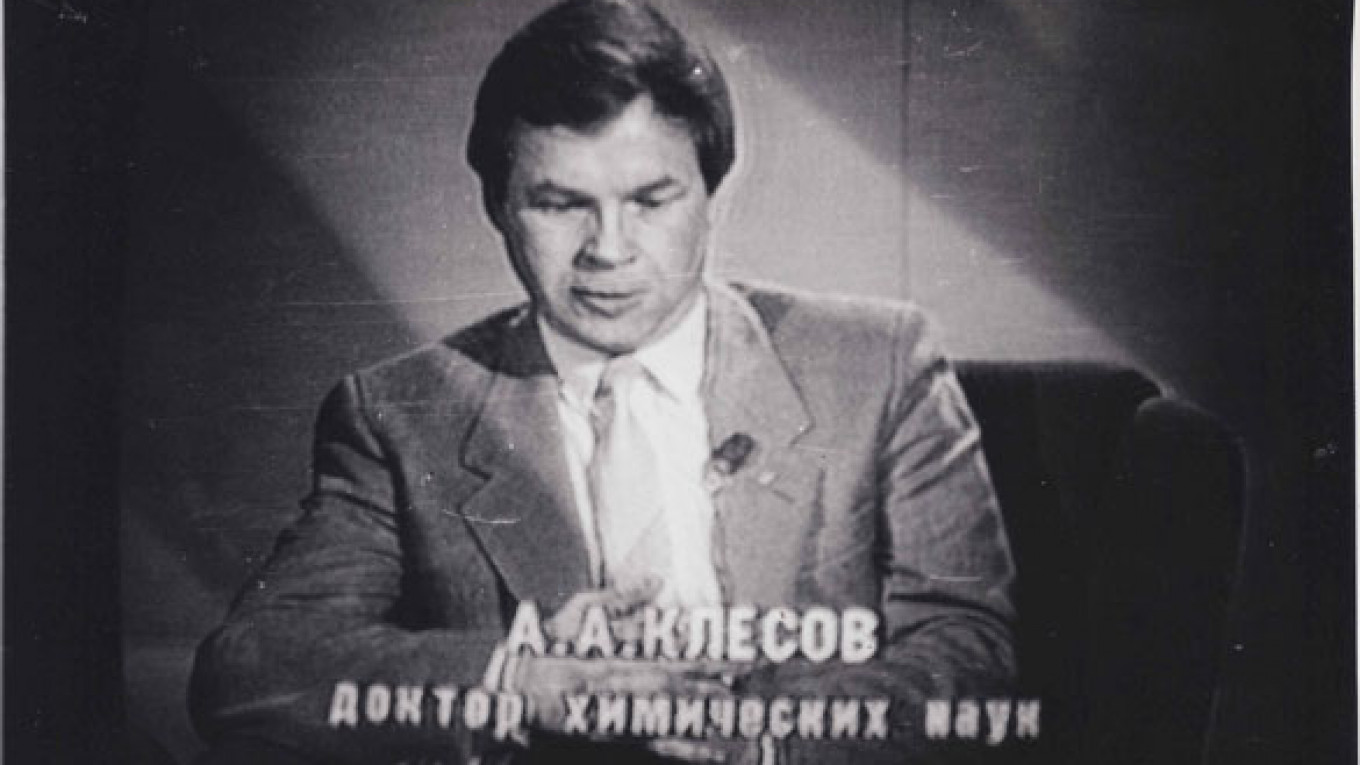

In late 1982, Soviet biochemist Anatole Klyosov typed in the web address of a Stockholm university and entered his password, only to be forced to wait impatiently for several minutes for the front page to load.

Sitting at the computer in a Moscow research institute, Klyosov experienced what he described later as the excitement of a cosmonaut on a space flight.

Back in the early 1980s, most Soviet citizens — just like the majority of the world's population — were unfamiliar with computers, let alone the possibility of using them to get in touch with people across the globe. Not even the omnipresent KGB was yet aware of the potential of the technology, which was only accessible to several hundred scientists worldwide at the time.

Klyosov describes the experience of his first web session — which made him one of Russia's first web surfers, if not the first — in an upcoming autobiography titled "Internet. Notes of a Researcher," to be published in Moscow next month. He provided excerpts from the book to The Moscow Times.

Klyosov's account provides a sharp reminder that Russia didn't always lag behind the West in high technology, a gap that President Dmitry Medvedev is trying to bridge this week with a trip to the high-tech capital of the world, California's Silicon Valley. Medvedev kicked off his trip with a meeting with California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger on Tuesday night.

In 1982, when Klyosov first went online, the Soviet Union, the United States and the handful of other countries experimenting with the Internet were all on the same level.

The web sessions, known back then as “computer conferences," "differed from the present Internet by speed and by the fact that very few people actually knew about it," Klyosov said in an interview by e-mail from the United States, where he has lived since the early 1990s.

Between 1981 and 1983, only six countries participated in computer conferences — the United States, Canada, Britain, Sweden, Finland and the Soviet Union, Klyosov said.

Connection speed was excruciatingly slow and prevented the use of graphics. "We drew pictures on the screen with crosses and zeros," Klyosov said.

It is not precisely known who holds the title of Russia's first web surfer. Oleg Smirnov, former head of the research institute that provided Klyosov with web access in the 1980s, said he could not remember who it might be, adding that there were other web users in 1982 whom Klyosov was not aware of.

Klyosov came to the All-Russian Research and Science Institute of Applied Automated Systems, known as VNIIPAS, in 1982 after he received an invitation from the United Nations to take part in an international computer conference on biotechnology scheduled for December 1983.

"It was hard to assess the significance of the event at that time," Igor Zudov, who was then-deputy head of the magazine Science in the U.S.S.R., said in a phone interview. "We could never imagine that a conference would lead to the creation of the World Wide Web."

VNIIPAS was founded in 1982 and initiated communication with computers in other countries the same year. It provided access to primitive teleconferences and foreign computer databases, as well as e-mail and file exchanges with foreigners for researchers, mostly affiliated with the Academy of Sciences, and industrial workers, who were only allowed access for work purposes.

After the conference ended, Klyosov continued to go online through VNIIPAS without notifying the authorities.

The KGB, which was widely known to be bugging phone calls and tracing teletype messages to foreigners, either did not know that Klyosov had unrestricted web access for years before moving to the United States in the early 1990s to work at Harvard University, or did not seem to be bothered by the fact.

"I believe they didn't even realize at the committee that one could pass over classified information using the Internet," Zudov said.

But Klyosov was still afraid of possible sanctions, so he decided to “raise public interest in computer conferences” and increase the number of Internet users in the Soviet Union, he writes in his book.

It was this idea that brought him to Science in the U.S.S.R., a magazine whose editor, the late scientist Georgy Skryabin, spent several weeks pleading with the authorities to let him publish what became the first report in the Soviet Union about the possibility of contacting people abroad via computers, Zudov said.

In the 1980s, VNIIPAS eventually established Internet connections with 11 countries.

Klyosov said he had many pen pals by 1984.

“Businessmen were looking for contacts with the Soviet Union, Swedish girls were inviting me to the sauna, and Rusty Schweickart, an American astronaut, was bombarding me with letters, looking to establish a teleconference bridge with the Soviet Academy of Sciences,” Klyosov writes in his book.

But still, in 1984, there were fewer than 400 people online across Europe during working hours, and the number dropped to a handful of people in the evenings, Klyosov said.

In 1988, a personal computer cost 15,000 to 40,000 rubles — "considerably more" than a dacha in the Moscow region, and 50 to 140 times more than the monthly salary of a senior researcher, Klyosov said.

Nowadays, Klyosov and his wife have six computers at home, at work and in their summer house in Massachusetts, and Klyosov admits to spending several hours a day on the Internet.

"I could have done without it, but what for? My productive work would have immediately slowed down," Klyosov said.

The activities of Klyosov and other early web users gave Russia a head start on the Internet in the 1980s. But it was largely wasted, and the country's path to cyberspace proved long and winding.

Only 5 percent of the Russian population, according to a poll by the Public Opinion Foundation in late 2002 and early 2003, said they went online at least once in the week that they were polled. The figure now stands at 32 percent, according to its latest survey.

The figure was confirmed by a Europe-wide survey by the Miniwatts Marketing Group, which placed Russia 45th among 53 countries polled, on par with Gibraltar, Romania and Turkey.

The leaders remain far off. In Iceland, Norway and Sweden, which took the top three places in the survey, 89 percent to 93 percent of the population are regular Internet users.

The European countries that Russia has managed to pass since its first brush with the Internet in 1982 are Albania, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cyprus, the British island of Jersey, Kosovo, Moldova and Vatican City.

Even Russian authorities acknowledge that the country's lack of Internet technologies is a cause for worry. The modernization-championing Medvedev put Silicon Valley ahead of a visit with U.S. President Barack Obama in Washington in what his economic adviser Arkady Dvorkovich said Monday was a sign of the Kremlin's priorities.

Klyosov said that, thinking back to the 1980s, he still puzzles over why the KGB ignored or remained ignorant of his web surfing activities for years. He blamed the KGB's sluggish nature for the misstep.

"There was no department for computer conferences at the KGB, and no one wanted to take extra responsibility or spend extra time at work," Klyosov said. “So nobody cared to think about that.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.