Speaking at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona in late February, Pavel Durov looked like a man in control.

Dressed all in black — a nod to the character of Neo in the film The Matrix — he strode across the stage. Like Neo, he was a programmer on a mission.

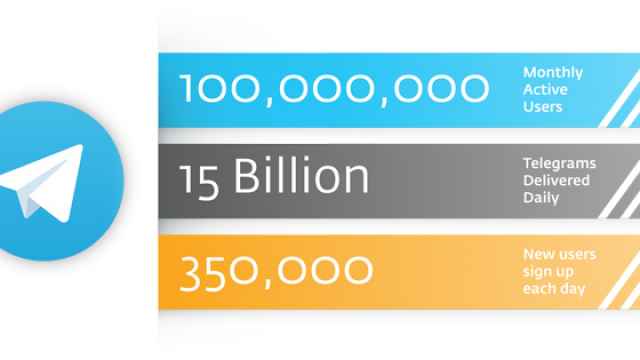

Pavel had come to Barcelona to announce that Telegram, the encrypted messaging service, had gathered 100 million monthly users and was gaining an impressive 350,000 new subscribers per day.

But his triumph was about more than just business success. It came about two years after the tech entrepreneur fled Russia after losing VKontakte, Russia's biggest social network, to allies of the Kremlin. Telegram is his revenge. Oozing confidence, he spoke to the audience: "Let me explain how we got here."

Coding Prodigies

From early childhood, Pavel Durov had little regard for figures of authority. While still in school, a young Pavel used his budding coding skills to hack the school's computer network. He changed the welcoming screen to: "Must Die" alongside a photo of his least favorite teacher. The school retaliated by cutting access to the network. But Pavel cracked the new passwords every time.

Pavel told his classmates he wanted to become "an Internet icon," Nikolai Kononov reported in his book The Durov Code. It was Pavel's brother Nikolai who would help him realize that ambition.

Four years Pavel's senior, Nikolai was a child prodigy. He was reading books by the age of three, and went on to become the two-time winner of an international programming olympiad. "He is a computer genius," said Anton Nossik, an Internet entrepreneur who has known the Durov brothers for years. In interviews, Pavel frequently refers to his older brother as his role model and coding mentor.

Pavel founded VKontakte fresh out of St. Petersburg State University in 2006, initially designed as a social platform for university students.

Nikolai began by advising his younger brother over the phone from Germany. But as VKontakte gained momentum, he returned to St. Petersburg and put his brains to the task as the company's chief technical officer. ??heir obsession was to make the Russian answer to Facebook faster and more reliable than its U.S. rival.

VKontakte's hiring policy was unashamedly ageist — the bulk of the mostly male team was in their early twenties. Future employees were asked at job interviews whether they drank (the desired answer was no) and parties were rare. Kononov described the atmosphere at VKontakte as one of triumphant ambition. "The nerds had conquered the world," he wrote.

From their headquarters at the prestigious Singer House in central St. Petersburg — which featured a medieval hall fitted with throne-like seats and torture instruments lining the walls — the team coded their way to success. By 2013, VKontakte had 210 million registered users, and was still growing.

Unwanted Attention

VKontakte's booming success was facilitated by an almost complete absence of regulation of the Internet market in Russia in the early 2000s. A staunch libertarian, Pavel embraced the vacuum. In ?° manifesto published in the Afisha magazine in 2012, he argued: "The best legislative initiative — is the absence of one."

VKontakte rapidly filled with hundreds of thousands of pirated films and music, becoming a focal point of cultural life — YouTube, Facebook and Spotify rolled into one. Critics said VKontakte facilitated the infringement of intellectual property rights by providing unpaid access to licensed films and music. It was also accused of distributing pornography.

At first, the Kremlin kept its distance. Pavel occasionally met with Vladislav Surkov, then in charge of President Vladimir Putin's domestic strategy. But the implicit deal seemed to be that VKontakte would be allowed to go its own way.

That changed in December 2011, when a wave of protests swept the country. Tens of thousands of Russians, many of whom formed part of the "VKontakte generation," protested against the rigging of parliamentary elections.

Facing the biggest uprising of Putin's reign, Russia's state security apparatus lumbered into action. The St. Petersburg branch of the federal security service, the FSB, asked VKontakte to delete the pages of seven groups using the site to coordinate and rally the protests.

Law enforcement had made previous requests to curb the activity of users who were deemed extremist — and VKontakte had reportedly given them backdoor access — but this time things were different.

Pavel responded with a resolute no, posting a picture of a dog in a hooded sweater with his tongue sticking out alongside a link to a scan of the official FSB request.

The tech entrepreneur would later tell Kononov: "I don't know why I then refused to close the groups' [pages.] Something in me resisted."

That same night, armed men in camouflage came to Pavel's apartment and pounded on the door, demanding to be let in. He refused.

On several other occasions, the FSB would try to curb VKontakte's activities. It demanded the closure of a group in support of opposition leader Alexei Navalny and Ukrainian activists who were supporting the anti-Kremlin Maidan protest movement in Kiev.

Pavel again went public with the requests on social media accompanied by photos of hairy dogs. His resistance bought him fame. He was embraced as a maverick who would challenge the establishment.

Nikolai, meanwhile, remained in the background. "He spends most of his life behind his laptop and other devices," Kononov told The Moscow Times. A handful of public photos show a middle-aged, bespectacled man with thinning hair and glasses.

The growth of Telegram

Buyout

The standoff with law enforcement took place amid a corporate dispute that saw Pavel gradually lose power over his company to two companies with ties to the Kremlin — Mail.ru and United Capital Partners.

Pavel treated the struggle for control with typical irreverence, posting a photo of himself giving the "trash-holding company Mail.ru and its attempts to take over VKontakte" the middle finger.

As Pavel's grip on the company slipped, law enforcement stepped up their attacks. In April 2013 Pavel was linked to an incident in which one of Vkontakte's white Mercedes had run over the foot of a police officer, even though Pavel claimed he did not drive.

Raids followed by investigators on VKontakte's office and Pavel's home. He was called in for questioning but didn't show up.

Days after the incident, United Capital Partners, a fund run by financier Ilya Sherbovich who had reported connections to? Putin ally Igor Sechin, was announced to have bought a 48-percent combined share of the company.

Pavel would lose the battle for control. In January 2014, he sold his 12-percent share in the company to Ivan Tavrin, an ally of Russian tycoon Alisher Usmanov, the owner of Mail.ru and one of Russia's richest men.

Mail.ru later bought UCP's share, too, giving it complete control over the company.

"[Pavel's ouster] sent a very simple, but powerful message to the Internet market," said Andrei Soldatov, an expert on online security. "Either you cooperate with the Kremlin or you're out."

By then, however, the Durov brothers had set up a plan B — and it involved leaving Russia.

Resurface

While still at VKontakte, Durov had secretly set up a new company called Digital Fortress. Its headquarters in Buffalo, New York, reportedly had enough server capacity to house one-third of VKontakte's traffic.

Russia's independent Dozhd television network broke the news to great scandal. VKontakte's staff, shareholders and Pavel himself denied the report and accused the station of fabricating the story to stir up tensions between shareholders.

"Even before the broadcast was over, my phone started ringing non-stop with people calling and asking: what are you doing? It the most aggressive reaction [to a story] that I've experienced in my entire career," Ivan Golunov, a journalist involved in the scoop, told The Moscow Times.

But Golunov had found evidence that a handful of Durov's programmers had already relocated to the United States. He said at least one of the programmers was still on VKontakte's payroll.

Asked to comment on the mystery project, Pavel had sent Dozhd's reporters a moving image showing a scene from The Social Network — a film about the creation of Facebook. In it, the character of Facebook entrepreneur Sean Parker gives two middle fingers to a group of venture capitalists in a shiny office building. Pavel Durov seemed to be plotting his revenge on the shareholders that were pushing him out of VKontakte.

In August 2013, Pavel pulled the rabbit out of the hat — the Durovs had been working on an encrypted chat service called Telegram.

Pavel provided the capital — he had reportedly left Russia with $300 million in his pocket from selling his VKontakte shares — and its "ideology." Nikolai was responsible for the coding.

The result is a James-Bond-meets-artificial-intelligence messaging service that rivals bigger players on the market like WhatsApp by promising to protect users from third party interference.

User data is encrypted and stored in several jurisdictions — making it difficult for third parties to access. A secret chat option allows users to send messages with self-destruct timers.

Pavel reportedly burns through $1 million of his own cash every month to keep the project going. He told Fortune magazine in an interview that he would start looking for investors in several years, but according to Telegram's website: "Making profits will never be a goal."

Privacy Is Priority

With Pavel himself functioning as a walking billboard for the service, Telegram needs little PR. The Durovs say the idea for Telegram was born out of their need to communicate privately while the Russian security services were breathing down their necks.

The timing of Telegram's launch also coincided with revelations on the snooping practices at America's National Security Agency leaked by Edward Snowden. Pavel has called Snowden — who, ironically, was granted political asylum in Russia — his "personal hero."

But history is looking to repeat itself, as Durov's company once again finds itself in the crosshairs of authorities. This time it won't be just Russia's security services asking for a backdoor, but those of governments worldwide.

China has already blocked access to Telegram. A Russian lawmaker called for a similar measure after it was reported that the terrorists responsible for a series of coordinated attacks in Paris last year used Telegram to communicate. Telegram's public channels service, which allows users to publish messages to unlimited audiences, was also accused of providing a recruiting and propaganda platform for Islamic State, a terrorist group banned in Russia.

Since then, Telegram has shut down 78 public channels being used by IS. But the function, famously used by Pope Francis, has also been embraced by civil rights activists who argue it allows citizens to bypass countries with repressive media laws.

Tech giant Apple has also found itself in a corner after the FBI demanded access to an encrypted iPhone belonging to a man involved in a shooting rampage in December that killed 14 people in San Bernadino.

Pavel has publicly supported Apple in its battle against the FBI saying: "Our right to privacy is more important than the fear of terrorism." But Apple seemed more willing to throw the Durovs under the bus. A chief lawyer for Apple in early March told the U.S. Congress that "one of the most pernicious apps that we see in the terrorist space is Telegraph [sic]. It has nothing to do with Apple."

He also called the service "uncrackable." Pavel is likely to consider this an endorsement of his service.

Band of Fugitives

While the standoff between privacy and security continues, the Durovs are not taking any risks.

The brothers and a handful of programmers, many of them Russian, live the lives of fugitives. Pavel reportedly alternates between three phones. Though the company is based in Berlin, its staff uproots to a new location every several months, staying in hotel rooms or accommodation rented through AirBnB.

With Telegram, the Durovs appear to have avenged the regime that saw them flee their country. It is an open secret that Russian top officials themselves use Telegram to communicate through the secret chat service without being snooped on by their colleagues.

But Putin's Internet adviser German Klimenko late last year issued a veiled warning, telling the Dozhd television network: "I am sure [that] either Telegram cooperates [with the security services,] or it will be shut down."

If Pavel's history and his love for The Matrix is anything to go by, his response to that ultimatum is likely to resemble Neo's answer to a deal proposed by his nemesis, Agent Smith. The agent promises to clear Neo of criminal charges if he provides the agent with information on rogue elements fighting the system.? "We're willing to wipe the slate clean, give you a fresh start," he says. "All that we're asking in return is your cooperation in bringing a known terrorist to justice."

"Yeah. Well, that sounds like a pretty good deal," Neo responds. "But I think I've got a better one. How about, I give you the finger?"

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @EvaHartog

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.