While the dust is still settling over the recent firing of two IKEA managers amid corruption claims, the former head of the Swedish furniture giant's Russian operations has packaged his love and hate for Russia in a new book.

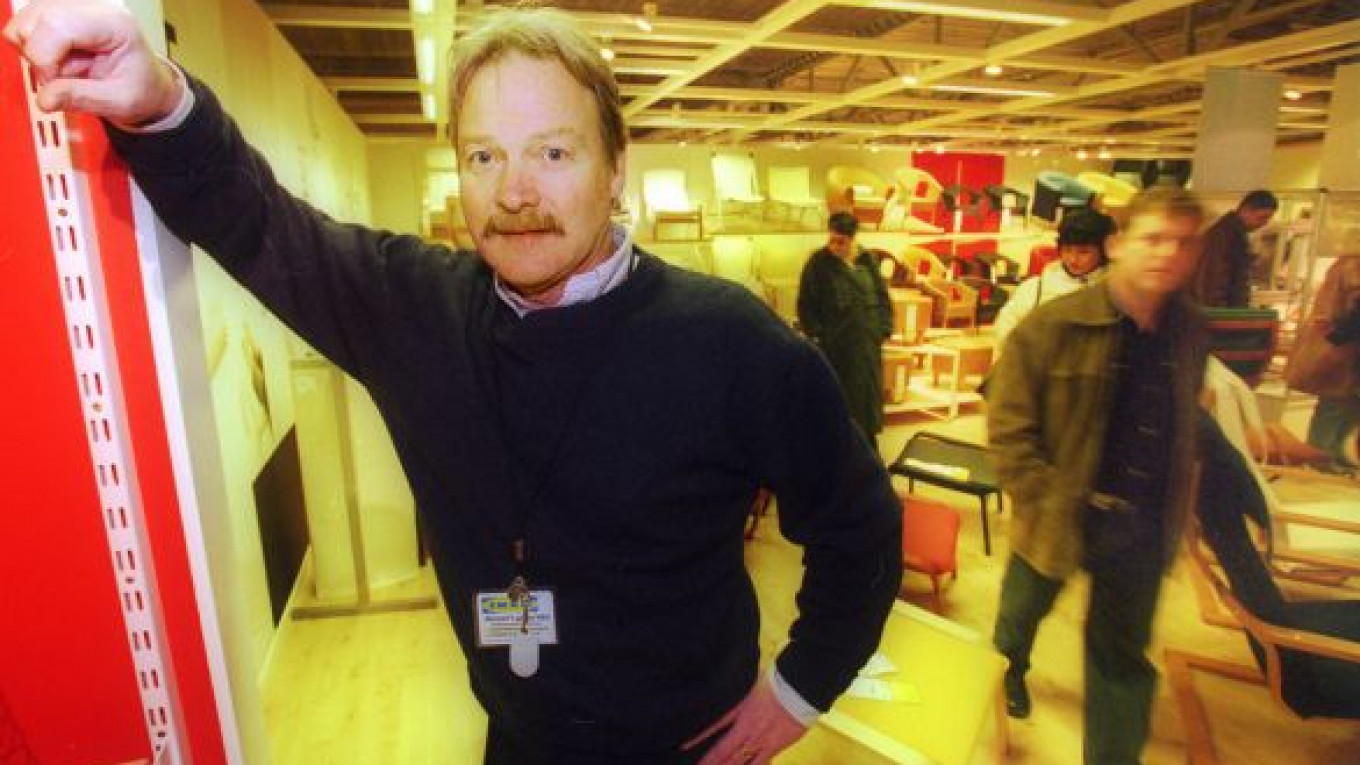

But Lennart Dahlgren, who stepped down in 2006 after setting up the first IKEA stores in Russia, holds no apparent grudge against the country, where he jumped through bureaucratic hoops, faced threats and treaded a fine line between IKEA's stringent ethics and Russia's "chaotic reality."

He said the "chaotic reality" pushed him to write down his adventures during sleepless nights for inclusion in the eventual book.

"When yet another mayor would go back on his previous promises, it would drive me crazy, but it was good for the book," Dahlgren said at the presentation of the Russian-language book in Moscow this week.

The book is titled "Despite Absurdity: How I Conquered Russia While It Conquered Me," and it differs significantly from the Swedish version "IKEA Loves Russia," which came out in November to a "rather silent reception," Dahlgren said. No English version of the book has been released.

The 230-page book offers short anecdotes, cultural stereotypes and rants about things like insolent black SUVs with flashing blue lights. Dahlgren optimistically concludes that Russia has a big future after a new generation replaces the one currently in power, whose members "took part in the development of five-year plans and later the explanations of why they have not been fulfilled yet again."

The book is hitting stores a month after Dahlgren's successor, Per Kaufmann, was fired along with Stefan Gross, IKEA's director for real estate in Russia. The company says the two "turned a blind eye" to a corrupt transaction between an IKEA subcontractor and a power-supply company to hasten the resolution of a power-supply problem at one of IKEA's malls in St. Petersburg. The decision was the first of its kind in the company's history and capped a scandal that unraveled after a series of articles in Swedish tabloid Expressen exposed the deal.

Dahlgren was thrust into Russia as he mentally prepared for retirement. IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad, who had long wanted to expand into Russia, sent him and his family to Moscow on Aug. 17, 1998 — the day that the Russian government defaulted on its debt, starting the 1998 financial crisis. Within months, flights "full of expat families" were fleeing Russia, taking their business with them, Dahlgren said. Amid the economic turmoil, Dahlgren got down to work, driving around Moscow to look for potential store sites.

While the book is chock-full of anecdotes about corruption, the tone is lighthearted and at times over the top. "I am waiting for the head of the Solnechnogorsk district, Vladimir Popov," Dahlgren writes at one point. "He is usually late in meeting with us, the simple businessmen. … Finally Popov arrives! He arrives in a huge elephant, with a flashing blue light tied to the elephant's head … and knocks Zhigulis and Volgas out of the way.

"Was it really like this? Since the time that I first came to Russia, it's hard to surprise me," he writes. "What I lived through in Russia is so beyond belief that hardly anybody will believe me."

Authorities in the Solnechnogorsky district of the Moscow region, where IKEA built a distribution center in 2003, became a problem after the dismissal of Deputy Governor Mikhail Men, who was working with the company, he said. He accuses then-district head Vladimir Popov of using the police to halt construction of the center and says work resumed only after IKEA contributed $30 million to assist elderly people and agreed to work with a contractor recommended by the regional government.

Popov, who lost elections last year and now works at the Moscow Agro-Engineering University, said the book is "far from reality."

Dahlgren "had one goal — to construct stores, preferably for free, without taking municipal interests into account," he told Komsomolskaya Pravda earlier this month.

Numerous attempts to open a store within Moscow city limits failed as a result of City Hall's unclear priorities, Dahlgren said.

Several attempts to build a store on Moscow's Kutuzovsky Prospekt were disrupted by smear campaigns, including the placement of flyers in neighborhood mailboxes that resembled a letter from Dahlgren on corporate letterhead. Mayor Yury Luzhkov then proposed that IKEA move into a newly built complex, but the company passed because the structure "was a futuristic architectural fantasy that did not have much to do with reality."

Although Luzhkov seemed interested in bringing IKEA's first Russian store to Moscow, talks stalled right away when the city demanded an "astronomical price tag" for the land desired by IKEA. "Buying land on these terms would make it impossible to keep low prices on products," Dahlgren said. IKEA went to the Moscow region, and Moscow held a grudge for years, he said.

Repercussions over IKEA's decision to break off talks were felt when the company was barred from advertising the June 2000 opening of its first Moscow region store in the Moscow metro because of "studies concluding that people have unstable psyches underground … so our ads could be dangerous," he said.

Dahlgren also linked City Hall with difficulties that IKEA faced building an off-ramp to its first store, in Khimki. Authorities said the off-ramp would desecrate a nearby war memorial.

No one at City Hall's press service was available for comment on the book Wednesday.

Dahlgren said he met regularly in a restaurant overlooking the Kremlin with a stranger in a green suit to discuss the problems surrounding IKEA's store in Khimki and to listen to gossip from then-President Vladimir Putin's inner circle. "I never knew his name or what he does," Dahlgren said, "but soon we had permission to build the off-ramp."

The off-ramp was built by a company recommended by Moscow regional authorities, but it took three times longer than necessary to build and cost $5 million more than it should have, Dahlgren said.

While some officials worked against IKEA, others, such as in Tatarstan, helped to open stores in record time. "It took less than a year between the first meeting with Kazan's mayor and the store's opening — a record impossible to break anywhere in the world," Dahlgren said.

Despite stereotypes to the contrary, Dahlgren said, thefts at Russian stores are fewer than in other countries, and Russians drink less at corporate parties. He added, however, that he made it a habit to drink a glass of milk before informal dinners with Russians, whom it is "inadvisable to compete with in resistance to alcohol."

IKEA's public struggles — which may have contributed to its brand recognition in Russia more than anything else — have been seen as a litmus test of sorts for the government, which has promised repeatedly to root out corruption.

"Officials regularly make public statements about increasing the war on corruption, bureaucracy and abuse of office," Dahlgren said. "But we did not notice any positive changes over all this time."

While some legislation has changed for the better, "the authorities have not," he said at the book presentation.

Dahlgren attempted to arrange a meeting between his boss, Kamprad, and Putin in 2005 but was told by a high-ranking official that it would cost $5 million to $10 million. "I sensed that it would be better not to get into that discussion any deeper," Dahlgren writes, adding that he is still unsure whether they were speaking seriously or joking.

The 83-year-old Kamprad — who threatened to stop investing in Russia last year over corruption problems and reportedly wept when informed about last month's St. Petersburg scandal — has yet to meet with Putin or his successor, President Dmitry Medvedev.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.