Kulik's radical actions attracted the attention of the mass media, and his notoriety played an important role in ushering Russian contemporary art out of the underground and into the streets in the 1990s. More than any other artist, Kulik brought contemporary art to the public eye and helped it take its current place in Moscow's cultural mainstream. Now his top-dog status has been cemented by "Oleg Kulik: Chronicle. 1987--2007," the first solo exhibition to ever fill all 10,000 square meters of Moscow's biggest exhibition space, the Central House of Artists.

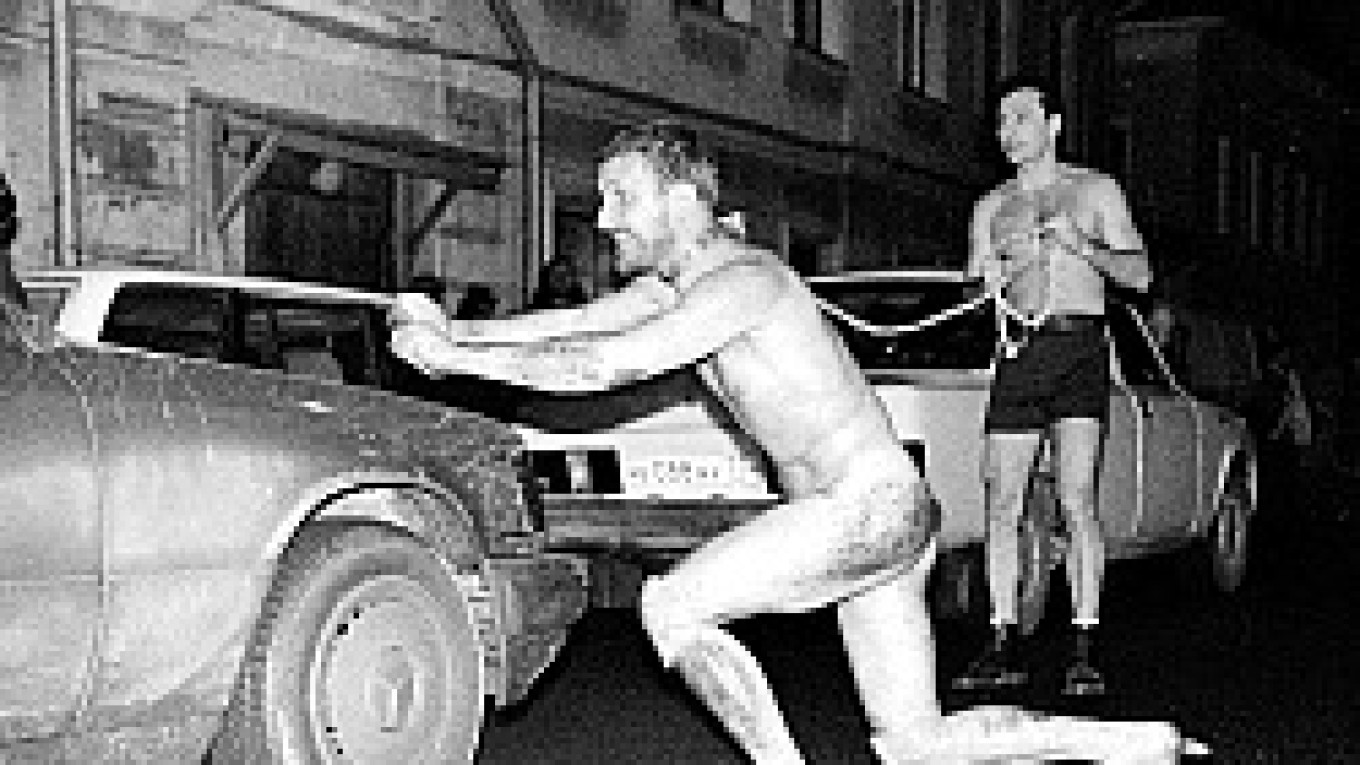

The yawning interiors of the big white box have been draped with sheets of black plastic to create a suitably raw setting for the show; the Central House of Artists is virtually unrecognizable as the bland backdrop of trade fairs it usually functions as. "Chronicle" covers two decades of Kulik's zoocentric, antirational art. It starts with the 1995 sculpture "Hot House Couple," a working greenhouse shaped like a bull and cow in coitus, where the male's penis is a sprinkler that irrigates the garden in his partner's womb. And it ends hundreds of meters later with videos of performances where, stripped and leashed, Kulik bayed and snarled at his audience.

A large portion of Kulik's output is immaterial, and the total area of "Chronicle" was dictated by pathos rather than necessity. Architect Boris Bernaskoni, the exhibition's designer, generously allotted each of Kulik's photography series and sculptures from the later part of his career its own spacious room. The only part of the show that feels crowded is the cluster of videos on the third floor, where screens have been installed in adjacent rooms with limited sound insulation. The resulting cacophony of Kulik's barks and onlookers' screams partially recreates the chaotic atmosphere of the original events.

Over the course of his career, Kulik has often criticized European culture's paradoxical, hypocritical attitude toward the natural world. He reminds his audience that although people depend on animals for sustenance, even companionship, the relationship is marked by human control and domination. Animals are symbols of impurity or evil in several Western and Russian mythologies, and the words "cow," "pig" and "dog" can be wielded as insults in more than one European language.

In many actions, Kulik employed these negative associations to strike back at civilization, bringing its inherent violence and hypocrisy to the surface. In 1996, when Kulik threatened to enter the presidential race as head of the "Party of Animals," he toured Moscow wearing horns and hooves, a satyr satirizing the political zoo of Russia's transitional period. He has appeared several times as a dog, a domesticated animal that people can either keep as a pet or train to attack others.

Kulik shocked the public by advocating interspecies love and outraged the art world when he bit a Swedish curator, but behind the stunts and scandals he is the kind of artist's artist whose work probes the possibilities of representation. "Windows," for instance, is an installation that tests the limits of the landscape genre. At one end of a vast corridor, a multiplex-sized screen shows a stretch of Mongolian desert as seen from the window of a moving car, while a transparent plastic square in the hall's center frames part of the scene. The moving image on the big screen may reveal more of the desert than a framed picture could, but is ultimately bound by the screen's edges. In "Windows," Kulik demonstrates the limitations of the landscape, just as he indicated the barrier between the artwork and viewer in his canine performances; in a variety of media, Kulik has champed at the bit of artistic practice, constantly pointing at culture's mishandling of nature and searching for the essence of the authentic experience.

No wonder, then, that Kulik gave up art a few years ago. Although the timeframe set by his retrospective's title is "1987-2007," the most recent work is 2003's "Gobi Test," a shaky and minimally edited video of the artist's trip to Mongolia. These days, Kulik wears a full beard and a Central Asian skullcap. He acts like a modern-day Tolstoy, repeating the 19th-century thinker's calls to abandon the complex trappings of culture.

Last year, Kulik escalated his adopted role as a New-Agey guru for the art world by organizing a series of conversations about faith and feeling, and curating a subsequent exhibition called "I Believe." But in a recent conversation, Kulik said that he had no intention to make more art or even curate after the run of his retrospective; all he had planned was a trip to Tibet.

"Oleg Kulik: Chronicle. 1987-2007" runs to July 29 at the Central House of Artists, located at 10 Krymsky Val. Metro Oktyabrskaya, Park Kultury. Tel. 238-9634.

… we have a small favor to ask. As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been unjustly branded as a "foreign agent" by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct assault on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. Our commitment to providing accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unshaken. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and you can be confident that you're making a significant impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Remind me later.