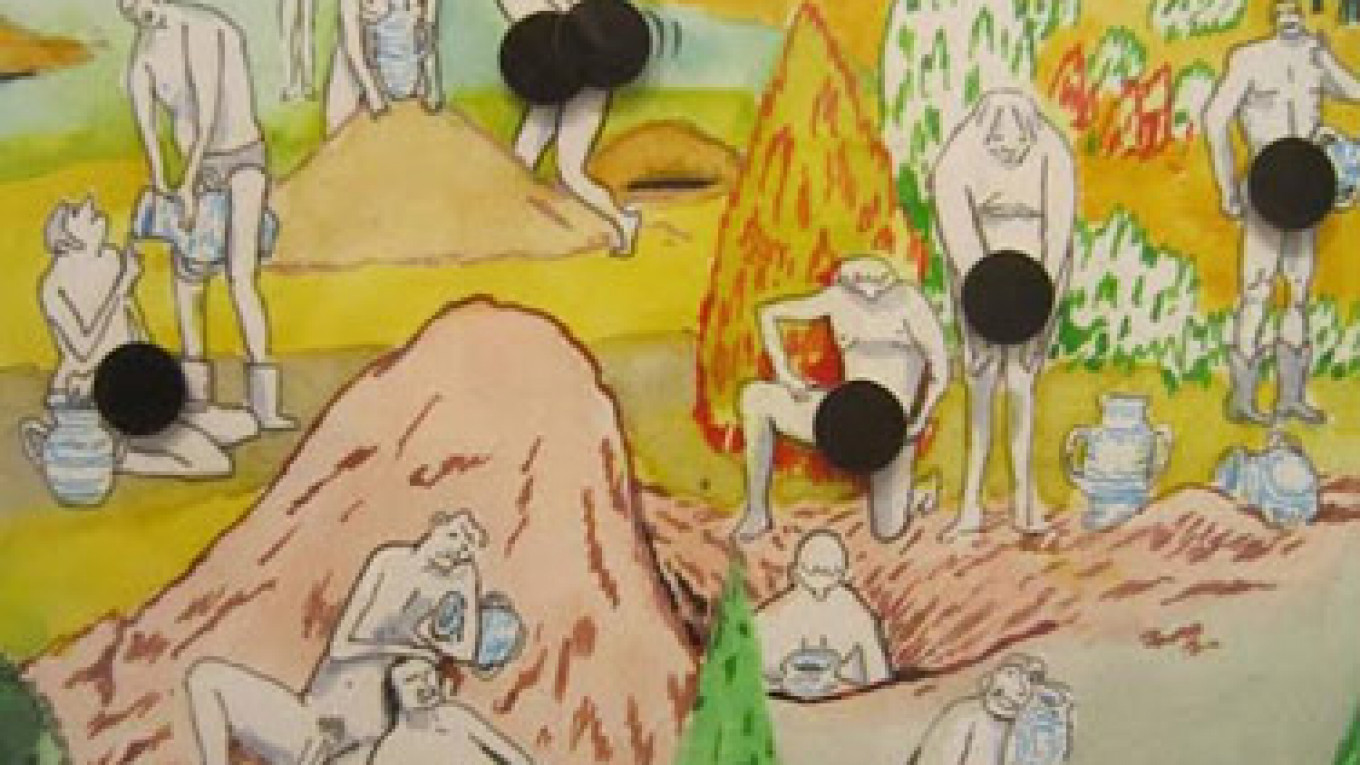

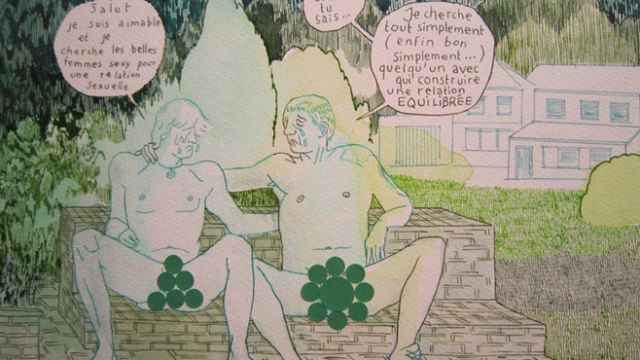

A Belgian and a German artist have had an exhibition of their graphic novel shuttered in St. Petersburg's Nabokov Museum. The artists, Dominique Goblet and Kai Pfeiffer, were displaying their work as part of an international comic, graphic novel and illustration festival called Boomfest, which has been held annually in St. Petersburg for nine years. Their illustrations depict a 50-year-old woman and her fantasies of several men who lurk naked in her "garden of paradise," crying and hoping for her to pick them like flowers.

When questions about nudity arose, the artists provided a range of humorous cover-ups. It wasn't enough: The exhibition, which had been scheduled to run until October 11, was dismantled on September 30. "Today, by request of the University of St. Petersburg, which the museum is subordinated to, the exhibition was closed and all our pictures were taken down," Pfeiffer wrote in a Facebook statement published the same day.

The St. Petersburg branch of the Goethe Institute, which backed the project, confirmed its closure. "We are very sorry that the exhibition of Kai Pfeiffer and Dominique Goblet was closed earlier than planned," PR coordinator at the Goethe Institute in St. Petersburg, Ekaterina Gottschalk, wrote to The Moscow Times in an e-mail.

Pink Panty Solution

Goblet and Pfeiffer explained by Skype that just before the exhibition was set to open, the museum director expressed reservations about the nudity in their drawings. The artists were bemused. "The Hermitage is full of naked people," Goblet said they responded.

When it became clear that the issue had become intractable, the pair decided to censor their works, but in a way that would be extremely conspicuous. First they decided to cover up the nudity on the green drawings with bright pink and orange panties. The museum objected and suggested traditional green grape leaves instead, said the artists. The pair experimented with black dots and "censor boxes," along with grape leaves and underwear.

The museum was not amused, said the artists. Two days later they called Dmitry Yakovlev, the Boomfest director, and asked him to come for the exhibition, which they'd taken down and packed up.

Yakovlev would not speculate as to why the show had been closed down. "It is a question for the Nabokov Museum," he said via VKontakte, the Russian version of Facebook. "When they were mounting the exhibition, they pointed out the problem, so the artists decided to put shorts on the characters. But in the end, it was not enough," he said.

Mutual Accusation Society

While the Nabokov Museum, which is under the direction of St. Petersburg State University, did not respond to a request for comment, in a statement published by St. Petersburg website sobaka.ru on Oct. 1, it accused Yakovlev of deceiving the curators — agreeing to bring one set of drawings and bringing another set instead.

Goblet and Pfeiffer dismissed this as "a lie." "We know Yakovlev sent all the images ahead of time." A promotional image used on the Goethe Institute's website for the exhibition additionally depicts the artists' graphic novel's cover illustration and contains nudity.

It is possible that the Nabokov Museum was simply being cautious, having been attacked twice in 2013. On Jan. 10, one of the house's windows was smashed and a bottle, reportedly containing biblical passages, was left at the scene. A few weeks later, on Jan. 29, the word "pedophile" was daubed on its walls.

Small museums are unprotected and afraid of offending visitors' beliefs.

"Extremists are really looking at what the museum does," Pfeiffer said. The museum curators at the Nabokov Museum may have been more concerned about nudity because of the attention it garnered in the past.

However, the artists argued that pre-emptively bowing to the demands of extremists is essentially saying 'the extremists are right.' "She [the museum director] was very displeased by my insinuation," Pfeiffer said.

Reading Tea Leaves

The main driving force behind the wariness appears to be the threat from Orthodox Christian extremists who are "generally the most active," said Sasha Obukhova, curator of the Archive Collection at Moscow's Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. However, gallery size, location, and a general feeling of uncertainty as to where the next blow will strike all factor in. "The general situation is such that museums are afraid of social reactions," Obukhova said via Skype. "Especially in St. Petersburg where this [Vitaly] Milonov is deputy," she said. Milonov is a conservative deputy infamous for being the driving force behind Russia's "gay propaganda" bill.

"This is mostly just museums protecting themselves," she said. "We know lots of events in Moscow and St. Petersburg that are very risky … some people will come and complain that this or that exposition offended their feelings." A 2013 law, passed in the wake of Pussy Riot's anti-Putin "punk prayer" in the Christ the Savior Cathedral, prohibits the offending of people's "religious feelings."

"The Church is everywhere," said Anna Nistratova, director of Nizhny Novgorod's contemporary art and street art gallery, the Tolk Gallery, citing the banning of Marilyn Manson concerts in June 2014. She suggested that Orthodox groups "feel they have the power to influence society."

Obukhova cited further legislative ambiguities. "Another law … says that the propaganda of homosexuality among children [also enacted in 2013] is forbidden — but no one knows what that means. In this case, everything can be offensive, just everything," she said.

The artists also wondered whether their works were perceived as "propaganda of homosexuality." Goblet and Pfeiffer suggested that one of their pictures had contained some imagery that could have been construed as homosexual, given that there were naked men in the garden together. "They [the characters] weren't gay before, but now they might be," Pfeiffer joked.

Finally, the problem could simply be that small museums feel vulnerable. Garage's Obukhova said, "Small museums are very uncertain of their exhibitions in general. The Nabokov Museum is small, it is not protected by city government, and the exhibition they were showing didn't belong to them." Obukhova said that Garage's status as a privately funded museum helps it make "risky decisions."

Nizhny Novgorod's Nistratova agreed. "Smaller galleries are not protected," she said. "We have only a young woman sitting there … anything could happen."

In this regard, she didn't consider the incident in St. Petersburg to be anything remarkable. "It happens all the time," she shrugged.

But one exhibition she deemed extraordinary was held in Tolk Gallery last year, and contained "pacifist" works by Russian and Ukrainian artists. "We were sure we'd have problems," she said. "But nothing happened. It was quite a surprise."

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.