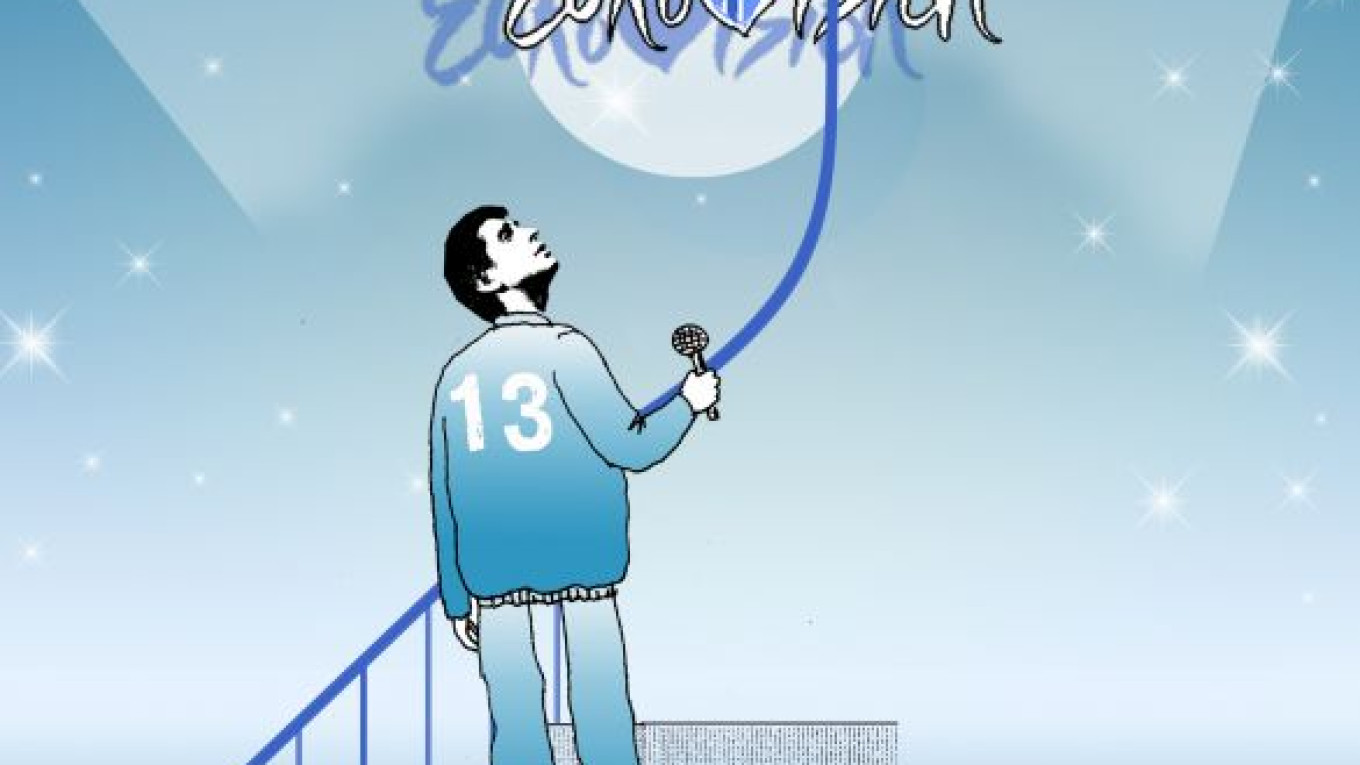

On Sunday, Russia chose Pyotr Nalich, a quirky singer who became famous through YouTube and isn’t part of the glitzy Russian pop scene, as its entry for this year’s Eurovision Song Contest.

Nalich and his band won a convincing 20 percent of votes, both from the public and the professional jury, which included two movers and shakers in Russian pop: songwriter Igor Krutoi and producer Maxim Fadeyev. But his performance could not have been less glamorous: His shirt and trousers were in need of an iron and the only special effect was a piece of paper that he pulled out of his pocket. And opinion was divided on whether he will cut it at the contest final in Oslo in May.

“Is this a sign that we will soon be sending random passers-by to the Eurovision?” Moskovsky Komsomolets asked. Its pop music expert, Artur Gasparyan, called Nalich’s chances “very moderate” in an interview with RIA-Novosti.

The 2008 Russia winner, Dima Bilan, told Komsomolskaya Pravda that he thought the song was “pretty weak.”

Nalich became famous in 2007 when he posted a song called “Guitar” on YouTube with a deliberately cheesy video in which he sat in a Lada and danced around a dacha. His initial success was probably based on novelty value, but Nalich — who studied opera singing at a music college — has gone on to give full-length concerts at big venues like Moscow’s B1.

He said Sunday that he entered the competition to get a wider audience but was so relaxed about the whole thing that he admitted that he didn’t even know when the final was.

His Eurovision song, “Lost and Forgotten,” is a simple, sing-along guitar ballad that isn’t a million miles away from last year’s winning song, “Fairytale,” by Norwegian singer Alexander Rybak.

It beat competition from Russia’s most desperate Eurovision wannabe: pretty boy Alexander Panaiotov, who made his fourth unsuccessful attempt. There were also a lot of interchangeable female singers in tiny dresses and a few oddballs, such as Oleg Bezinskikh, who sang in an operatic falsetto with backing dancers sprayed silver.

The biggest cheer went to a group of elderly women called Buranovskiye Babushki, who come from the Udmurtia republic and wear traditional embroidered dresses and coin necklaces. Their act involved a little dignified dancing on stage by the six singers, who were all victims of Soviet dentistry.

While Nalich made it from the Internet to the cheesiest music stage in Europe, Soviet-era pop star Eduard Khil has inexplicably moved in the opposite direction to become a hit on YouTube.

Almost 2 million people have watched a video of his song “I’m very glad that I’m finally coming home,” after it was seized upon by American hipsters. Fans of what they call the “Trololololo Song” have set up a web site where you can sign a petition asking Khil, 75, to go on a world tour.

The song originally had lyrics about a cowboy riding over the prairie, but they were deemed un-Soviet so Khil simply warbles along to the tune.

The incredibly cheesy video is now a viral hit and got even more publicity when Christoph Waltz, the Oscar-winning actor in “Inglourious Basterds,” mimed to it on an ABC television show in the United States.

It’s a strange twist of fate for Khil, a besuited, clean-cut crooner, who was awarded the title of People’s Artist of Russia but perhaps never quite made the top echelon of stars. Let’s hope he makes some money from it, since he told Komsomolskaya Pravda last month that his pension only stretches to pay household bills.

And I hope he never realizes that there is an element of sneering to his newfound fame. He told Life News that he had never heard of his Internet popularity, “but what can I say, it’s pleasant. Thanks for the good news.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.