"I said to the bus driver 'I'd like to send my wife to Leningrad.' He replied: 'I sympathize. I'd like to send mine to Kamchatka. Or to the moon, instead of Gagarin.''' So goes a typically witty line in Sergei Dovlatov's "Pushkin Hills." Unfairly and inexplicably forgotten in English, Dovlatov is experiencing something of a revival, as not only was his "Pushkin Hills" translated into English in 2013 on the 30th anniversary of its publication in Russian, but he may also quite possibly become the first Russian writer to have a street named in his honor in New York.

This translation of "Pushkin Hills," which is considered by many to be his most humorous work, was translated by Dovlatov's daughter Katherine. She described the novel as "the most personal of my father's works." On the back cover of the book, a recommendation from The Observer gushes that "Dovlatov's writing is simple but witty, with a hint of nostalgia; you can't help but smile throughout." This might be something of an understatement, while reading on the Moscow metro, I attracted some curious stares as I laughed out loud at the hilariously black comedy contained between the pages of the? slim paperback.

I was first introduced to Dovlatov while studying Russian literature at university and have been a fan ever since. After smirking and giggling through "The Compromise," "The Suitcase" and even "The Zone" — Dovlatov's satirical novelization of his time as a prison camp guard during Soviet times — I soon exhausted the supply of Dovlatov's work which had been translated into English. Until December 2013, when I heard about "Pushkin Hills." I seized upon it eagerly and was not disappointed.

"Pushkin Hills," describes the summer of Boris Alikhanov, an unsuccessful writer and a hopeless alcoholic, a classic example of the Russian literary "superfluous man." His wife, Tatyana, has divorced him and plans to emigrate to the West with their young daughter, Masha. Boris decides to take a summer job as a tour guide at the Pushkin Hills reserve in Mikhaylovskoye. ?

Most of the novel describes Boris' summer as a guide, his dealing with the ridiculous questions of tourists, like: "Excuse me, where did Pushkin and Lermontov have their duel?" and his carousing with his alcoholic landlord. However, there is a constant feeling of dread present in the background — his wife and only child are leaving, and there is nothing he can do about it. He admits to himself that while he does not feel any great sentimental attachment to his homeland, he cannot leave it. He would miss "my language, my people, my crazy country although I couldn't care less about birch trees." In the end, Tatyana and Masha leave and Boris sinks back into alcohol-fueled apathy. "Pushkin Hills" displays Dovlatov's wit, his writing is dry and the tone is nostalgic.

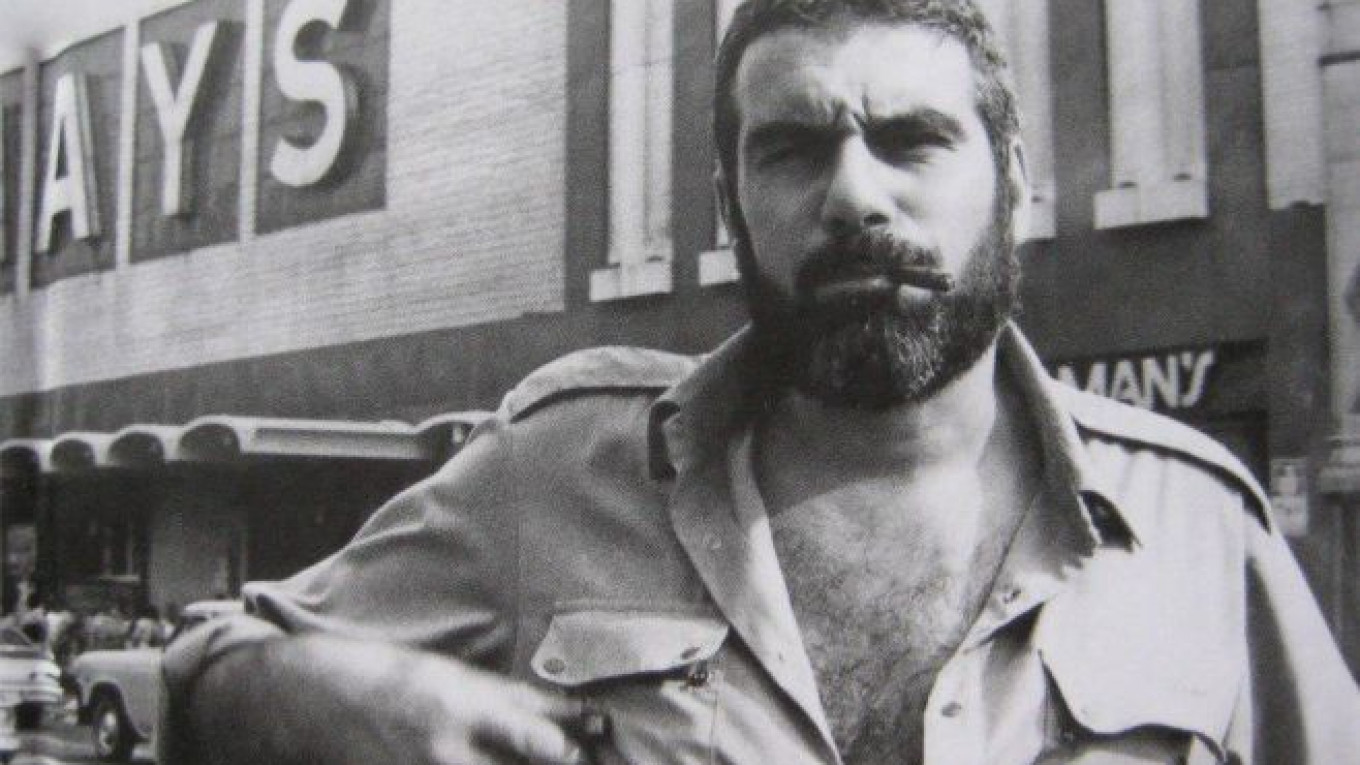

Dovlatov arrived in the U.S. in 1979 and quickly became a leading figure among Russian literary emigres, after Brodsky and Solzhenitsyn, he was the most famous contemporary Russian writer in the U.S. His work had been censored in the Soviet Union and read in samizdat. He settled in the Forest Hills area of Queens, New York, the second-largest Russian-speaking area in the city. His stories were published in The New Yorker — he was only the second Russian wrier after Nabokov to receive such an honor. Kurt Vonnegut wrote to Dovlatov jokingly complaining that "I was born in this country and fearlessly served it during the war, but I still haven't managed to sell a single story of mine to The New Yorker. And now you come, and — bang! — your story is published at once …? I expect much from you and your work."

Part of the so-called "third wave" of Russian emigres, he edited a Russian weekly called "The New American," in which he wrote about Russians living in the U.S. He received letters and drawings from Brodsky who praised Dovlatov and claimed that he was easy to translate because "the decisive thing is his tone, which every member of democratic society can recognize." Brodsky also said, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that Dovlatov was "the only Russian writer whose works will be read all the way through."

Ironically, as soon as Dovlatov started to gain popularity in his native Russia, around 1989, his star began to wane in the U.S. He did not live to see the collapse of the Soviet Union, dying of a heart attack in 1990. However, along with the new translation of "Pushkin Hills," a campaign is underway to name a street in Dovlatov's honor in New York. A group of Dovlatov fans last year approached the board of the building in Forest Hills where Dovlatov lived — where his widow and daughter still reside and maintain his archive and workspace — and requested to place a plaque, commemorating the writer on the building. The plaque was approved and now adorns the building, along with similar plaques in other places the writer lived in Tallinn, Ufa and St. Petersburg.

Encouraged by their success, the group started an online petition, which now has more than 13,000 signatures, asking New York City Council member Karen Koslowitz to add "Sergei Dovlatov Way" to the "63rd Drive" street sign. The city council will soon make its decision, and those wishing to sign the petition can do so at change.org. If this goes ahead, it will be a historic occasion — the first time a Russian writer has been honored in such a way. There are few writers who deserve such a revival of interest and recognition in the English-speaking world more than Sergei Dovlatov.

Contact the author at g.cuddihy@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.