"I wrote this book for a very narrow circle of readers," Ulitskaya said in a recent interview. "It's a very personal novel. Its success was something of a surprise."

But last year, when film director Yury Grymov approached Ulitskaya with a proposal to bring her book to the screen, the author gave in. "Yury seems to be the man who can give it a more universal appeal, who can be, so to speak, its translator for the broader audience," she said. "After all, cinema has certain possibilities that prose doesn't have."

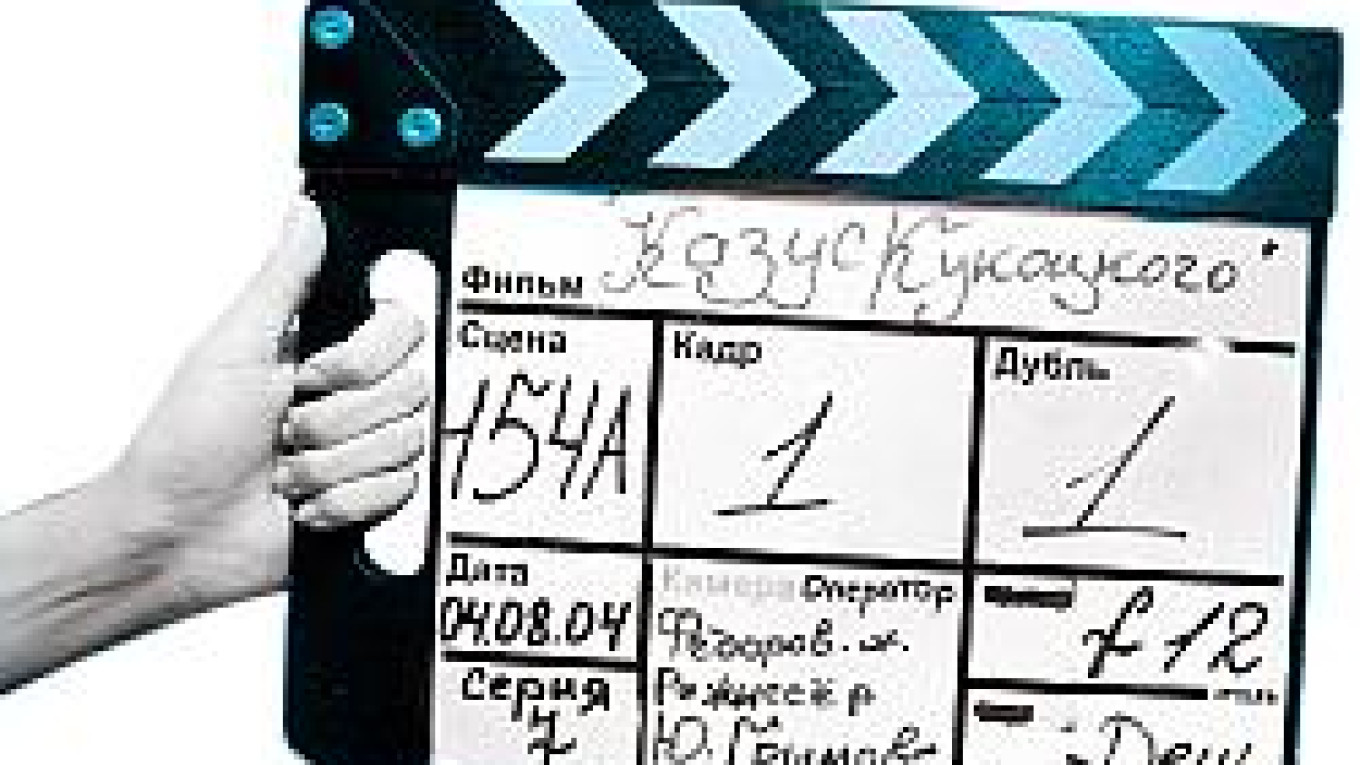

An NTV television channel production, the 12-part miniseries is slated to air in November 2005. But thanks to its director's reputation and a star-studded cast, anticipation is already high. The veteran of some 600 short films, including ambitious MTV-style music videos and commercials selling everything from magazines to cellphone services, Grymov was praised in the 1990s for making better use of his actors than many feature films of the time. His 1998 movie "Mu-Mu" stirred up talk for its unconventional treatment of a schoolbook story by Ivan Turgenev, and his 2001 feature "The Mastermind" (Kollektsioner) met with critical acclaim, silencing those who claimed he was not cut out for full-length films.

Taking after Ulitskaya's novel, Dmitry Kotov's screenplay spans several decades of Soviet life. Pavel Kukotsky, the scion of a long line of physicians and a gynecologist and obstetrician himself, has a gift: He can see the insides of his patients. His X-ray vision affords him unique diagnostic and healing powers, but suffers when he eats too hearty of a breakfast and disappears for as much as several days after he makes love. Upon discovering this, Kukotsky relinquishes earthly pleasures until he falls in love with a patient after seeing her intestines, marries her and adopts her daughter, Tanya. The private and tortured life stories of these characters form the backbone of Ulitskaya's book.

On location late last month at a Moscow hospital, the lighting crew was busy setting up a scene in which Kukotsky takes a bottle of pure alcohol from his medicine cabinet and downs a glass. Nearby, two prop hands were laying out an enormous map of the universe for a scene to be filmed later that day. Taking a moment from showing Yury Tsurilo, the actor playing Kukotsky, how to slam down the empty glass, Grymov praised his cast and crew for staying up to date with a rigorous schedule ever since the cameras got rolling on his birthday at the beginning of July.

"I want the best professionals on this movie," the director said. "If you switch on the television and watch current Russian series, it's a disaster. It's not because of the genre -- there's nothing wrong with the series itself. David Lynch managed to make a masterpiece out of 'Twin Peaks.' But it has to be taken seriously. It's a work of art."

Much of the load in "The Kukotsky Case" has fallen to Tsurilo, the St. Petersburg actor best known for his starring turn in Alexei German's 1998 film "Khrustalyov, My Car!" (Khrustalyov, Mashinu!) as a military doctor accused of treason during Josef Stalin's anti-Semitic campaigns. Dressed in a white doctor's smock, Tsurilo had small, professorial spectacles perched on his nose.

"Most of the script is made up of my lines," the actor said, calmly lighting a cigarette. "See this pile of sheets? That's what I had to learn by today. I also had to take up smoking. Kukotsky smokes, and I needed it to come naturally."

Less easy to convey is Kukotsky's magical gift of being able to see his patients' bodies as if lit from the inside in luminescent coils. Asked whether digital effects were going to be used, Grymov's response was categorically negative. "It would have looked cheap," he said. "It's something no one else sees, and we'd be cheating to let the audience have a glimpse of it. After all, it's a miracle. We'll have to do it differently, through dialogue and the narrator's voice."

Given the fact that Kukotsky never discusses his gift with anyone, bringing it across through dialogue would seem a dubious task. It was not until classic leading man Alexei Batalov agreed to read the voiceover text after at least a decade of refusing cinematic work that the question was resolved.

Vladimir Filonov / MT Last Wednesday, Yury Grymov, right, and assistant director Stanislav Yegerev resumed filming at Moscow's Institute of Physics and Chemistry. | |

Grymov's costume designer, Masha Danilova, heartily agreed. "We want the costumes to be unnoticeable. It's the actors' faces that matter," she said. "We go for real old shoes, real old dresses -- things that are comfortable to wear, things that live onscreen but don't attract too much attention."

Though he refuses to disclose his overall budget, Grymov has clearly had the luxury of thinking big. The film will feature more than 600 actors, among them stage and screen star Yelena Drobysheva as Kukotsky's wife, last year's Golden Mask winner Chulpan Khamatova as his stepdaughter Tanya, and well-known Moscow actor Karen Badalov as Kukotsky's longtime friend Ilya Goldberg. Given the film's historical sweep, some of the characters had to be cast several times over, with Ilya Goldberg's twin sons played by five different actors -- one set of infant twins, one set of teenage twins (this proved to be the most difficult casting call, since the boys had to be identical and able to act) and one adult who will portray them both.

"You can feel the creativity on the set," said Andrei Feofanov, the record producer and film composer who wrote the series' score. "The people there are obviously eager to work. They're having a good time." Apart from Moscow and St. Petersburg, Grymov will transport his cast and crew to the Black Sea resort of Sochi and even to the Canary Islands, where he plans to film the mystical afterlife "desert" that Kukotsky's wife sees in her sickbed visions. "The whole last episode will be shot in the desert," he said.

But turning to the private family drama of the novel itself and to conceptually unified editing, Grymov intends to keep the scale small. "The colors of the movie are soft -- black and white, soft brown, gray," Danilova said. "When there's a color highlight, it always means something. For example, Tanya, Kukotsky's stepdaughter, wears red because she's the author's alter ego, and the splash of red is one way to stress that."

Scurrying around the set, the extras virtually blended in with the hospital staff, who were carrying on their business as usual aside from curious glances in the cameras' direction. "Ladies with case histories!" Grymov shouted, jumping out from behind his monitor and tossing his long hair. "Please, hold them tighter. Press them to your chests. Are we ready? Aaand -- action!"

Alexandra Borisenko and Maria Baker contributed to this report.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.