More than 100 years later, the building next door would be home to a young Sergei Naryshkin, the future deputy prime minister whose climb to the top ranks of the Kremlin hierarchy involved not a drop of revolutionary spirit but the ability to assimilate himself into a system that would ensure his success.

With the quiet manner and discipline of an avowed technocrat, Naryshkin betrays no sense of personal ambition, despite a slow and steady rise from local Komsomol leader to loyal member of President Vladimir Putin's intimate St. Petersburg circle.

Yet as Putin hints that he may not relinquish power after the presidential election in March, moving to the post of prime minister instead, Kremlin watchers are training a keen eye on Naryshkin, a man whose career mirrors Putin's own to a startling degree.

"This is a hypothetical scenario that journalists thought up," Naryshkin said at a recent conference, when asked about the chances of Putin naming him as successor. He speaks softly but sternly, breaking into easy smiles with the deceptively shy demeanor that Putin exhibited early in his Kremlin career.

"I have no real plans, aside from working at what I'm currently working on," Naryshkin said. "But if the future president makes a decision similar to the one the current one did and offers me a post personally, then I would agree to it."

Putin brought Naryshkin to Moscow in February 2004, plucking him from the ranks of the Leningrad region administration to make him deputy head of the presidential economic council.

Naryshkin's subsequent swift rise to power made him one of the first in a cadre of reserves called up by Putin -- men who profess a strong allegiance to the president while lacking the years in Moscow that have prompted bitter infighting among his siloviki backers.

His ability to remain outside the clan warfare by juggling competing interests makes him the ideal consensus presidential candidate, analysts said.

"Naryshkin is neither the protege of any of the siloviki, nor has he had any great conflicts with any of them," said Alexei Makarkin, an analyst at the Center for Political Technologies.

Indeed, those who know Naryshkin describe him in nearly identical terms, as if reading from a readied script. The deputy prime minister, they say, is hardworking. He is professional. He is approachable. And he discreet.

These qualities, longtime friends said, are what distinguished Naryshkin from the crowd and prompted the attention of the local Komsomol youth group and later of the KGB.

And the qualities may be just what Putin is seeking in the next president. Addressing United Russia's congress earlier this month, Putin said he would consider becoming prime minister only after the party won December's parliamentary vote and a "decent, competent, modern person" was elected president.

It appears to matter little that Naryshkin fails to register in public opinion polls and receives considerably less airtime than Prime Minister Viktor Zubkov or First Deputy Prime Ministers Dmitry Medvedev and Sergei Ivanov, the three men widely believed to be at the top of Putin's list.

Forty percent of Russians plan to vote for whomever Putin decides to back, even if they do not know the person's last name, according to a recent poll by the independent Levada Center.

Naryshkin's name, however, would resound with the electorate anyway. He shares the same last name as the elite family that was a staple of the tsarist court and included Natalya Naryshkina, the mother of Peter the Great, the Westernizing tsar who is Putin's idol. Portraits of the Naryshkin family line the Tretyakov Gallery's walls, and their names fill the history textbooks read by Russian schoolchildren.

Naryshkin's friends and former colleagues differed on whether the minister came from the same bloodline.

"It's only now that he's become interested in it," said Alexei Pastyukhov, a childhood friend and champion of Naryshkin. "He tried to find out and, yes, they are descendants."

A former professor of Naryshkin's at the Leningrad Institute of Mechanics said he liked to play up the name. "He's not linked to the famous Naryshkins, but sometimes he says he is," said the professor, who asked for anonymity so that he could speak candidly about the powerful politician.

The White House, which handles press matters for Naryshkin, declined repeated requests for an interview with him.

Son of the Party Elite

Born in 1954 in the heart of postwar Leningrad, Naryshkin grew up on Fontanka, one of the city's most coveted addresses, where he shared a small apartment with his parents, grandmother and brother.

Acquaintances flatly refused to say what his parents did, with the former professor saying only, "His family, let's put it this way, was a workers' family" -- hinting that his father was in the Communist Party elite.

Pastyukhov said the young Naryshkin excelled in the prestigious school they attended together, and their circle of friends devoured the literature that began to appear in Soviet journals in the early 1970s.

"The times weren't bad. Stalin was long gone, so were the repressions. Sure, they sent Sakharov away and Solzhenitsyn abroad, but people weren't scared anymore," Pastyukhov said.

"After school, we would call each other and say, 'Let's go to Letny Sad," he said, referring to the gardens that lay just across the canal from Naryshkin's house. "And we would walk and talk about the books we'd read. We could read Bulgakov and Updike. None of this was available before."

Igor Tabakov / MT Naryshkin attending an investors conference on June 18 with former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell and Kudrin, his former boss at St. Petersburg's city committee for economics and finance. | |

Naryshkin would never work as an engineer. An experience of a different kind during his institute years would come in even handier as he went on to build a career in politics.

In 1978, he was named first secretary of the institute's Komsomol, the Communist Party's youth wing. The key appointment indicates that he had attracted the attention of the powers that be.

"It was a really important position," said Pastyukhov, now a physics professor at St. Petersburg's State University of Technology and Design. "He didn't have that much interest [in the Party] while in school, but someone noticed him and asked him to be secretary."

It was also during that time that Naryshkin met his wife, Tatyana, a classmate also specializing in engineering.

Naryshkin quickly won influential friends through the Komsomol post, said Vladimir Kudryavtsev, who worked at the institute during Naryshkin's time there and also served in the Komsomol leadership. "He was smart, and you could always to talk to him. He had a calm personality, and people were drawn to him," he said. "He had friends, and they moved him along, helped him.

"It wasn't ambitions for himself that he had," Kudryavtsev added.

Blank Spot in Resume

Naryshkin's official biography abruptly goes blank from 1978 to 1982, and friends say he was sent to Moscow to study, hinting at KGB recruitment.

"He came to the department specially to say goodbye to us," Kudryavtsev said. "Few people do something like that in their lifetimes. They usually just run away.

"He didn't say where he was going, and the next time I saw him, it was on television," he said.

Pastyukhov said he only knew that his friend had been sent to Moscow but had no further information.

"If someone goes into the system, it's thanks to his personality. If someone does go into it, they'd never talk about it, they'd tell no one," he said.

"Sergei never talked about his work. What he did in Moscow, I could only guess."

Naryshkin resurfaced in 1982, when he was appointed deputy rector of the Leningrad Polytechnic Institute. Then, in 1988, he left for the Soviet Embassy in Brussels, at a time when the city, home to NATO headquarters, was abuzz with talk of looming revolutions in the East. Naryshkin's official title was "expert to the state science and technological committee."

Several former high-ranking Western and NATO diplomats said they had no recollection of Naryshkin, who Pastyukhov said acted as third secretary at the Soviet Embassy.

Naryshkin served in Belgium through 1992, missing the upheavals at home as the Soviet Union disintegrated.

Yet his return to Russia's political scene proved seamless, as he immediately joined the team of St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak, the liberal lawyer from whose administration Putin and those around him launched their political careers.

Working for three years in the city committee for economics and finance, he fostered close ties with Putin and those who would become his key ministers and advisers. At the time, the committee was headed by Alexei Kudrin, now a fellow deputy prime minister and the finance minister.

Focusing on attracting foreign investment to St. Petersburg, Naryshkin worked alongside Putin, who headed the committee for external relations.

Even those who profess to know Naryshkin closely are unaware of the relations he maintains to people within Putin's circle -- yet another unknown explained away by his ability to remain discreet.

"He knew the president back from working in the Leningrad government," said Pastyukhov, who visits with Naryshkin once every few months. Naryshkin is godfather to Pastyukhov's 2-year-old son, Mikhail. "Since Putin sent for him, their relations must be good.

"But, quite rightly, he never talks about these things. Once we asked him, 'Do you know Vladimir Vladimirovich?' He said, 'Yes.' 'What is he like?' 'Great.' And that was that."

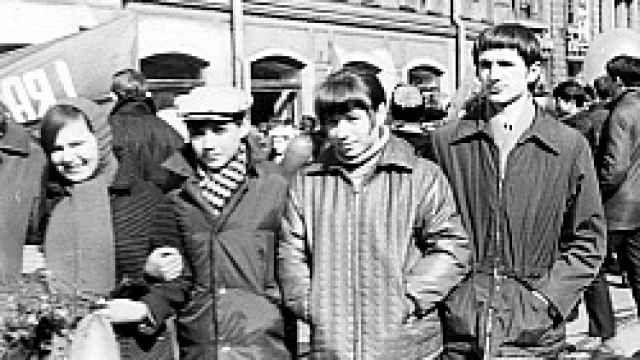

Courtesy of Alexei Pastyukhov Naryshkin, right, and Pastyukhov, second left, in St. Petersburg in 1971. | |

The bank attracted major clients as multinational firms quickly learned that connections were key to winning privileged contracts in a city slow to adapt to the country's new capitalist spirit.

Naryshkin would use those links in his next incarnation, as head of the Leningrad region's investment department, where he remained for one year before moving to chair the region's committee for external economic and international relations -- a post he would hold for nearly six years until called by Putin to Moscow.

"He proved himself to be very businesslike, a well-educated person," said Vatanyar Yagya, a former top adviser to Sobchak. "All initiatives that he took, in terms of both domestic issues and fostering external relations, were actively upheld by the Leningrad region administration.

"Above all, he's a good organizer and very easy to communicate with," he said.

During his time in the Leningrad region administration, Naryshkin oversaw enormous investments in the region, bringing in Philip Morris, Caterpillar and Ford, which all built factories in the area. Ford, among others, was one of Promstroibank's main clients.

"[Naryshkin] consistently advocated for the strict enforcement of laws and agreements from both the side of the business and the government, as well as for a level playing field and transparency," said Leo McLoughlin, managing director of Philip Morris in Russia and Belarus.

Meteoric Rise in Moscow

Since moving to Moscow in 2004, Naryshkin's rise can be described as nothing short of meteoric.

After a monthlong stint as deputy head of the presidential economic committee, Naryshkin was named deputy chief of staff of the Cabinet in March 2004. He was promoted to Cabinet chief of staff just six months later and holds the position to this day. That move saw him replace Dmitry Kozak, another Putin ally, who was named presidential envoy to the Southern Federal District in the reshuffle before being called back to Moscow last month as regional development minister.

In 2004, Naryshkin began to appear on the roster of some of the country's largest companies. He was named to the board of directors of Sovkomflot, the state-owned shipping company whose chairman is Putin aide Igor Shuvalov.

Naryshkin himself is chairman of state-owned Channel One television as well as of the new Unified Shipbuilding Corporation.

And he is highly placed on Rosneft's board, acting as first deputy to chairman Igor Sechin, Putin's powerful deputy chief of staff.

"He's highly professional, market-oriented, and a nice person," said a high-ranking source at Rosneft, who asked not to be identified because he was not authorized to comment on personalities.

Naryshkin was widely believed to have been placed inside the White House staff to keep an eye on then-Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov.

His promotion from Cabinet chief of staff to deputy prime minister in February -- a reshuffle that presaged Fradkov's replacement in September with new Prime Minister Viktor Zubkov -- was what first got him noticed outside the corridors of power.

Since then, Naryshkin has acquired an ever-expanding portfolio. Charged initially with overseeing foreign trade and CIS relations, he now oversees everything from the country's 556 billion ruble ($22.3 billion) investment program in Siberia and the Far East to the continuing construction of the East Siberian-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline.

Ever a consensus figure, Naryshkin has also chaired a series of meetings aimed at seeking compromise over competing ministries' ideas of what should be included in a long-awaited bill defining the country's "strategic industries," where foreign investment will be limited.

Yet it is not his political tasks that bring Naryshkin, however rarely, into the spotlight. Indeed, he has given just three long interviews to the media since moving to Moscow, always focusing on the mundane subject of administrative reform. What has seen him splashed across the front-pages and leading prime-time newscasts is another quality that binds him to Putin -- a love of sports. Naryshkin heads the country's gymnastics federation and, a keen swimmer like his teenage daughter, Veronika, he heads the All-Russia Swimming Federation as well.

In September, Naryshkin appeared alongside Ivanov on state-run television to congratulate the women's tennis team on winning the Federation Cup.

"My father never brought up the subject of his work life with his family, even less so, changes in career," his son, Andrei, a businessman in St. Petersburg, told Izvestia in an interview earlier this year. "Lately, I've heard of changes in his career only from the television news."

Naryshkin made a rare appearance in the society pages of Kommersant this week, photographed dancing with a woman in the midst of surprised onlookers at a party in Moscow's club The Most to celebrate the opening of the Bolshoi Theater's season.

Yet Naryshkin, like Putin before him, appears to work hard at keeping a low profile. After a conference of the European Association of Businesses earlier this month, Naryshkin hopped downstairs to the ground floor cafe of the Baltschug Kempinski hotel, sipping orange juice as he spoke with a conference participant.

There was not a bodyguard to be seen as Naryshkin got up from his table and walked toward the exit, hopping into a black sedan with tinted windows, blue light wailing as he sped away.

Editor's note: This is the sixth in a series of profiles of possible presidential candidates. Previous profiles can be read on The Moscow Times web site, www.themoscowtimes.com/doc/special_reports.html.

Resume

White House | |

Born: Oct. 27, 1954

Place of Birth: St. Petersburg

Education: Leningrad Institute of Mechanics, degree in radio engineering, 1978; Petersburg International Management Institute, degree in economics, 1997

Advantages: Close to Putin and his St. Petersburg circle, reputation as effective bureaucrat, good relations with foreign investors, famous last name, lack of outward personal ambition could make him ideal "weak president" to strong prime minister

Disadvantages: Low public profile, links to KGB and Putin's deputy chief of staff Igor Sechin could draw him into one Kremlin clan

Notable quotes:

"I don't see any sign of political instability in Russia. In fact it's a very stable situation." Speech at a foreign business conference, Oct. 16, 2007

"While I sympathize with a party, like most of the Cabinet members I am not, I repeat, a party member." Interview with Interfax, Sept. 27, 2007

"We must acknowledge that the events around Yukos have influenced the Western business community's perception on activities in Russia. We want these things to happen as rarely as possible, and I hope this will be the last," Speech at a Russian-French business event in Paris, June 3, 2005

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.