At Moscow's Kazachya Lavka, or Cossack Store, you don't need to be rich to be a Cossack. Their fake-fur version of the famous red papakha hat will set you back about $10. The full regalia, from head to toe, and including the horsemen's infamous nagaika leather whip, will cost the ruble equivalent of about $100. Today, the store has branches in several large Russian cities and its online shop delivers throughout the country.

While it might be a boon for small business, the widespread availability of Cossack garb comes at a price. In May, a group of men in papakhas attacked anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny and members of his Anti-Corruption Fund at an airport in the seaside town of Anapa. More than 20 men splashed the group with milk and a brawl ensued. In the aftermath of the incident, there was considerable confusion over the hecklers' identities — even within the Cossack community.

The leader, or ataman, of the local Anapa Cossack group, Valery Plotnikov, denied they had been part of his 98-member-strong crew. He told media that "real" Cossacks had actually tried to break up the scramble that had broken out. Another regional former Cossack ataman, Vladimir Gromov, said the men's outfits were nothing to go by. "Anyone can buy a papakha at any souvenir stall," he said.

Other Cossack leaders sided with the assaulters. The head of the Taman division of the Kuban Cossack troops Ivan Bezugly, defended the Cossacks and told the Ekho Moskvy radio station that Navalny himself had "provoked" the fight by insulting a Cossack colonel. And yet another man who identified himself as a Cossack was widely cited in the media as saying the attack on Navalny had been politically motivated.

The commander of a Cossack unit on active service in the Kharkov region, Ukraine, on June 21, 1942, watching the progress of his troops.

"We just wanted to show them that there is no room here for Navalny who lives on American money," the man who identified himself as Dmitry Slaboda was quoted as saying by the Govorit Moskva radio station. Several requests for comment from Slaboda by The Moscow Times went unanswered.

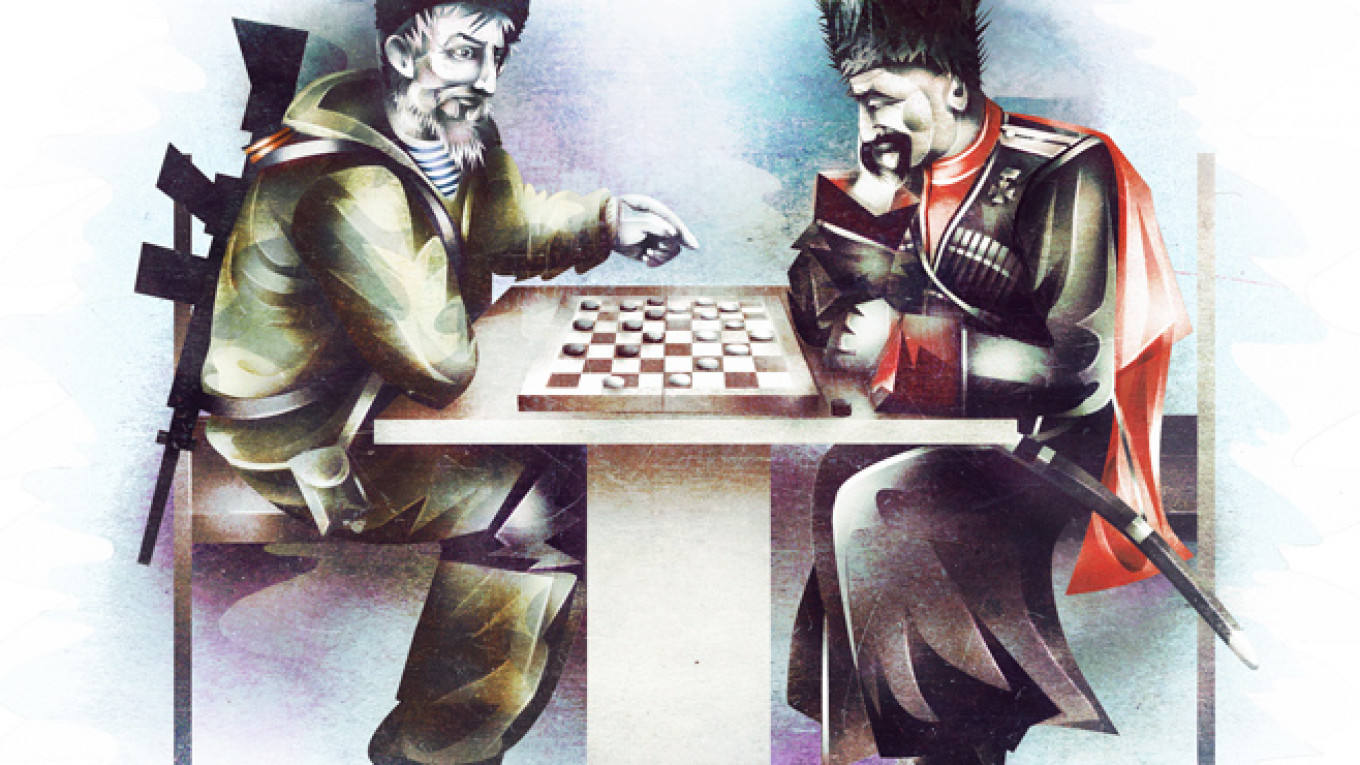

The who's-the-real-Cossack questioning that followed the incident goes beyond a simple matter of uniform. The attack on peaceful opposition activists, including women and children, has fed concerns that the Cossacks' romanticized past is being used to legitimize the actions of Kremlin-backed paramilitary groups. Ahead of parliamentary elections in September, it's not just opposition-minded Russians who are worried — some traditional Cossacks are too.

Rehabilitation

Cossack culture was all but extinct when then-President Boris Yeltsin issued a decree encouraging its revival in the 1990s.

The Cossacks had served tsars for centuries, lending their sabers to help conquer Siberia, the Caucasus and Central Asia in return for land and privileges. Loyal to the Romanov dynasty and the Orthodox Church, they fought on the losing side against the Red Army in 1917. After suffering defeat, hundreds of thousands of Cossacks were killed and persecuted under the Soviet policy of "Decossackization."

Yeltsin's decree called for the restoration of Cossacks as an "ethno-cultural group." By then, there were very few Cossacks left. Instead, the vacuum was filled with men of questionable Cossack ancestry, lured by a romantic vision of horsemen on the southern steppes. "The average Cossack was a middle-aged man who daydreamed about patriarchal values, unbridled masculinity and the glorious pursuit of imagined ancestors," says Brian Boeck, a historian who researched the Cossacks' rehabilitation in the 1990s.

In subsequent years, the Kremlin's return to conservative values and a brand of militant patriotism under President Vladimir Putin has made the deeply conservative and religious Cossacks a natural ally. Under Putin, registered Cossack organizations have been set up across the country and championed as a symbol of patriotism. Today, Cossacks' sense of patriotism, in some cases, runs ahead of the Kremlin's.

Bezugly, the Cossack ataman, late last year reportedly presided over the burning of effigies of U.S. President Barack Obama and Turkish President Recep Erdogan in the Kuban region at a rally in support of Putin.

And in the lead-up to Russia's annexation of the Black Sea peninsula Crimea two years ago, Cossacks in black woolen and fur hats stood guard at the Crimean parliament and manned checkpoints across the peninsula. Later, under the direction of Don Cossack ataman Nikolai Kozitsyn, they streamed into eastern Ukraine to fight against Ukrainian government forces. There, they were joined by local converts, attracted by the glamourous uniforms, the Cossacks' weapon supplies, and, according to many reports, good salaries.

Cossack regiments in the early 20th century

Inside Russia, Cossack patrols have become a kind of volunteer morality police. In Krasnodar, the southern region where the attack on Navalny and his team took place, they were even put on the region's payroll in 2012. Their increased presence was widely seen as an attempt to keep in check an increasing number of migrants in the region bordering the restive Caucasus region. And even though they had no authority to conduct arrests or carry firearms, the message was that the Cossack figure alone would provide police with a tool of intimidation less constrained by the burden of public accountability.

"What you can't do, the Cossacks can," then-governor Alexander Tkachyov was cited as telling police when he announced the creation of Cossack patrols.

The pouring of state money into local Cossack organizations has come under attack following the Navalny incident. In 2015, roughly 1 billion rubles ($15 million) was sidelined for Cossack groups in the Kuban region, the RBC newspaper reported. Some are now questioning the legitimacy of funding groups with a reputation for close links to local crime. "Most of these Cossack squads consist of local criminals," says commentator Maxim Shevchenko. "The kind of riffraff that behave like militias on behalf of local oligarchs. Real Cossacks don't behave in this way."

Make Culture, Not War

According to Vladimir Gromov, who served as the ataman of the Kuban Cossack Army for 17 years, paying Cossacks for serving alongside regular Russian police and military is not the issue. "No one works for a thank you," he told The Moscow Times. At the same time, he believes the Kremlin's focus on incorporating the Cossacks into federal structures has overshadowed the traditional cultural and spiritual aspects that are central to Cossack identity.

"There is the government on one side. And Cossackdom on the other. They enter into agreement, fine," he says. "But it shouldn't define Cossackdom."

Gromov cites a rich culture of song and social traditions, including "respect" for women and the elderly, as central to being a Cossack. Some of those traditions veer close to anachronism. As an example of proper Cossack conduct, Gromov said in a widely reported tweet that female smokers should be "flogged" with a Cossack whip as a way to discourage others. The tweet was later deleted.

Above all, honor and constraint are central to Cossack conduct, says Gromov, denouncing the Navalny episode. "If Navalny is guilty of breaching Russian law, there are law enforcement agencies that can and should prevent crime," he says. "What do the Cossacks have to do with this? But the image that has stayed in people's heads is that of Cossacks."

Already, Ella Pamfilova, the head of the Central Election Commission, has denounced the activities of so-called groups of rhyazhenniye, or fake, Cossack groups. She said there had been "an increase in aggressive behavior of such groups toward ideological opponents on the eve of electoral campaigns." Regular law enforcement has been turning a blind eye to these rogue Cossack groups, she said.

Milk is thrown on opposition leader Alexei Navalny and his associates outside the Anapa Airport in southern Russia on May 17.

The rhyazenniye label — used for Russian medieval-era jesters and nowadays is often used negatively to describe those who wear a costume that is not their own — has been met with resistance among the Cossack community. In an online statement, Nikolai Doluda, chieftain of the Kuban Cossacks, has called Pamfilova's statement "incorrect and unacceptable."

"It not only offends the feelings of various generations of Cossacks and their families," he said. "But it undermines the authority of all Russian Cossacks."

One of the reasons for that hostility could be the Cossacks' own interest to maintain a degree of obscurity as to who is, and isn't, a "real" Cossack. In a census conducted in 2002, around 7 million Russians identified themselves as Cossacks, which could be taken as a sign that the Cossack revival initiated in the 1990s has been successful. But, according to historian Boeck, the Cossack caste has largely been extinct since the 1920s.

"More individuals who claim Cossack ancestry today remain outside the official Cossack organizations than those embraced by them," Boeck says. "So even the Cossack atamans might not be viewed as 'real Cossacks' by most residents of the region."

According to former ataman Gromov, describing groups as rhyazhenniye also does little to explain away the incidental wrong behavior of Cossacks. "There are good Cossacks and not such good Cossacks," he says. "In that sense, Cossacks are just like any other people."

Contact the author at e.hartog@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter at @EvaHartog

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.