If the ongoing investigation into the downing of a Russian civilian airliner over Egypt's Sinai Peninsula on Oct. 31 concludes that a bomb destroyed the plane, the Kremlin will have to react — but its options are constrained by logistical and political realities on the ground.

So far, it appears that President Vladimir Putin and his administration have not decided how they want to spin the disaster. After initially dismissing the possibility of a terrorist attack, motivated by Russia's intervention in the Syrian conflict, the government has suspended all flights to the Sinai.

"The likelihood of a terrorist attack, naturally, remains one of the reasons this could have happened," Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev told newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta on Tuesday, explaining the decision to suspend flights.

According to Russian political analyst Yury Barmin, "it is relatively easy to convince Russians now that an alleged terrorist act is a sign of how effective air strikes have been, and that they can't stop when victory is one step away."

But Russia's air campaign, though impressive in several ways, has not yet succeeded in turning the tide in favor of embattled Syrian President Bashar Assad, who requested Putin's support in his 4 1/2 year struggle against a wide array of rebel and militant groups opposing his rule.

Meanwhile, Russian society has become increasingly polarized by the campaign. A Levada Center poll released late last month found that 53 percent of respondents supported Putin's policy in Syria, while 22 percent opposed it. The number of undecideds had dropped by half from September to 24 percent.

Though analysts said that the Russian government does not respond to public pressure on foreign policy, a significant shift in public opinion could put the Kremlin in an awkward position if Russians begin calling for a ground offensive or outright withdrawal.

The core of Putin's dilemma is that his military isn't capable of supporting a larger operation in Syria, especially one involving ground forces. He is likewise politically unable to pull out of Syria. Though he could pursue cooperation with the Western coalition, it would require a shift in strategy.

"Introducing ground troops in any meaningful numbers would be dangerous and, frankly, difficult for a Russia whose out-of-area logistics capabilities are already overstretched," said Mark Galeotti, an expert in Russian military and security affairs at New York University.

"Withdrawal is not yet an option and there's little real scope for more cooperation [with the Western coalition in Syria]," he said, arguing the Kremlin's next move is likely more of the same, with a few flashy cruise missiles launched from the Caspian Sea "duly packaged on Russian TV as a fitting and devastating revenge, but no lasting or major change to strategy."

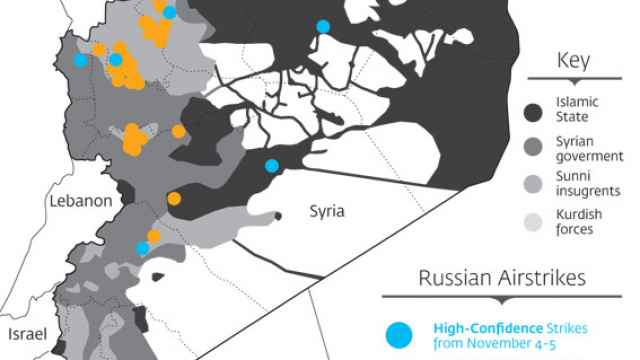

Russian air strikes Oct. 27 ?€” Nov. 5.

No Good Options

Although it is possible that Putin could use the Sinai tragedy to mobilize the Russian public in support of a large-scale ground operation in Syria, his ability to do this would be greatly limited by logistical shortcomings as well as potential for severe public backlash if things went wrong.

Russia currently has deployed in Syria about 50 aircraft flying air support missions for Assad and conducting air strikes on positions held by groups standing in opposition to him. There have also been reports that Russia has deployed a very limited number of ground forces to Syria.

"Russia's problem is that they cannot surge and cannot sustain logistically a large-scale ground operation. … 5,000 men is their limit and they need 20,000 to 30,000 new troops for [an Assad] offensive to succeed," said international affairs expert Vladimir Frolov.

Even if Russia was able to surge in such numbers, it would be a hard sell to the Russian public, which is willing to go along with anything the state media says until there is a direct impact on their lifestyles ?€” say, reservists being called to fight in Syria ?€” Frolov argued.

A second option, seeking closer coordination with the Western-led anti-ISIS operation also bombing targets in Syria, would be difficult in that it would require a change in strategy in Syria to align with the Western coalition against Assad ?€” undermining the Russian operation's stated justification.

Barmin said a slight escalation of Russia's force strength is most likely, but that "it is still unlikely that we are going to see a ground operation in Syria, it seems that it would be a recipe for tragedy."

According to Mikhail Barabanov, the editor-in-chief of Moscow Defense Brief, a monthly magazine published by the Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technologies, a local defense think tank, any Russian escalation in the conflict would be limited.

"It is possible that Moscow will have to increase the size of its air force grouping in Syria, and deploy limited numbers of 'technical' ground troops ?€” artillery units, missile troops, etc. ?€” in a similar style to the Soviet participation in the Spanish Civil War," Barabanov said.

Regardless of the policy choice, Frolov argued, "public opinion will stay right where the Kremlin wants it. ?€¦ There is no demand for accountability on foreign policy, and the Kremlin is pretty much free to act as it sees fit."

Karina Pipiya of the Levada Center said that Russian public opinion can be expected to grow increasingly polarized over the Syria conflict, but that a terrorist attack would only contribute to growing sentiment that Russia is "a besieged fortress" forced to respond to threats from abroad, giving Putin more room to maneuver in Syria.

Contact the author at m.bodner@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.