Cognitive dissonance is the state of discomfort one experiences when confronted with behavior or attitudes that conflict with and challenge one's beliefs about how the world is ordered. It's the feeling you might get if, for example, you were to see the Dalai Lama kicking a dog.

Or when you see dedicated, intelligent political leaders hoping to make a positive difference in Russia reach nonsensical conclusions and undertake inconsequential actions in trying to further their cause. There is no pleasure in criticizing well-intentioned people. But wrongheaded decision-making serves no one. As they say: It's a dirty job, but somebody's got to do it.

It was reported last week that leaders of the RPR-Parnas opposition party held a feedback session on their recent unsuccessful Kostroma election campaign. The lessons drawn from their electoral efforts apparently were that they needed to shorten the name of the party, use better-designed campaign literature and abandon the tactic of meeting with voters in their courtyards.

Legal filings to shorten the name of the party have been made because, according to party chairman Mikhail Kasyanov, the current name is too cumbersome and difficult for voters to identify.

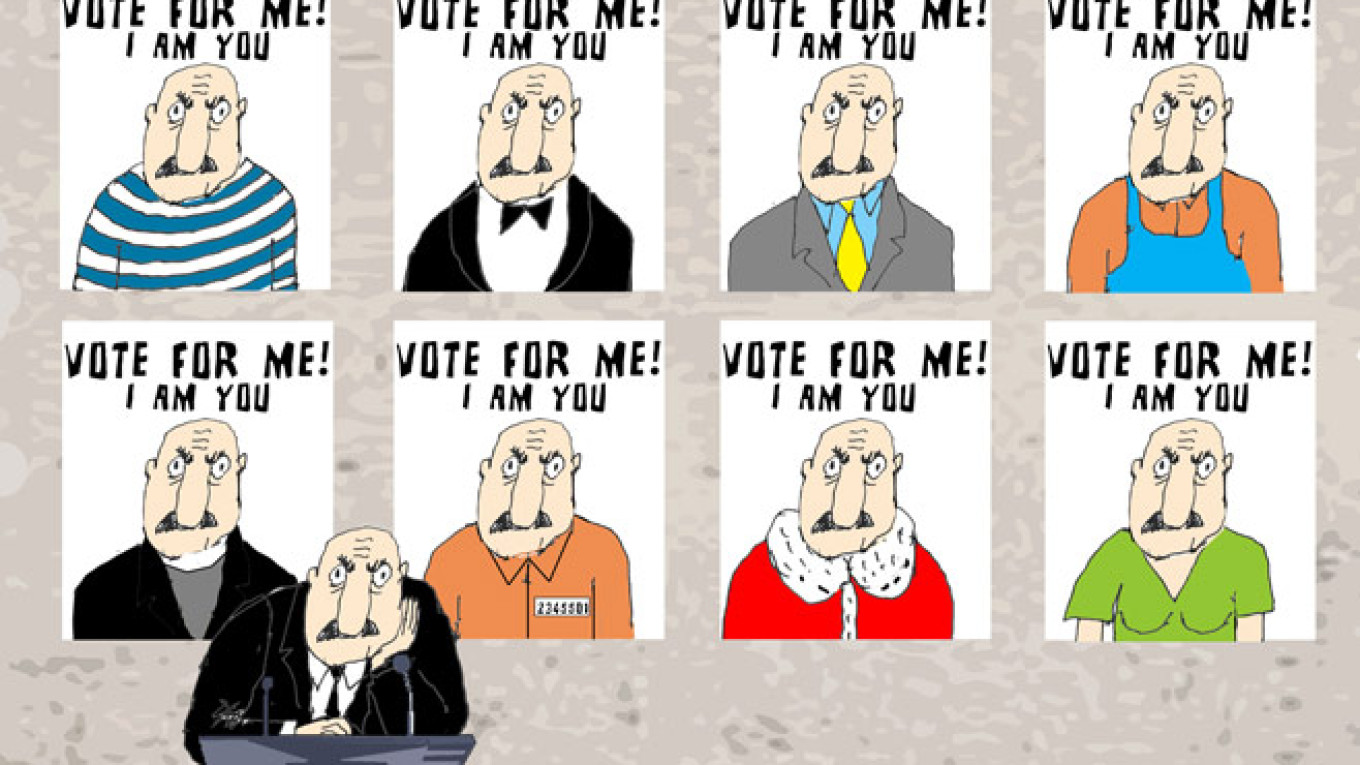

The party most certainly does have an identification problem, but it has nothing whatsoever to do with its name. The identification problem for voters is understanding what the party stands for. This is because the party has never made a serious effort to build its brand in any meaningful way that would resonate with citizens.

What to do to rebrand the party was an issue party leaders faced long before the Kostroma election, but to believe that a positive brand can be established through a name change and more appealing campaign literature belies a reliance on only the most superficial comprehension of what branding a political party entails.

There are examples to draw from in this regard. Some years ago, the Yabloko party branch in St. Petersburg recognized that parties out of power, especially those which register barely a ripple in the mind of the electorate, need to operate between elections more as NGOs than as political parties. Under Maxim Reznik's leadership one of the things the party branch did was align itself with the civic movement to prevent the building of the Gazprom tower in the city.

It did not attempt to usurp the leaders of the movement, but actively joined with the campaign, helping it to collect signatures on petitions and reaching out to other organizations to assist in strengthening the coalition of organizations opposed to the construction.

To be sure, such active civic involvement has its risks as well as rewards for a political party. It probably was a major factor in keeping Yabloko off of the ballot for the 2007 regional assembly elections. But they nevertheless continued their work — building their brand — and it paid off four years later.

When they had to collect signatures to gain entry to the ballot for the 2011 elections, their civic engagement work provided them with a much larger pool of activists to enlist support from. More importantly, it had established them as a party that stood out from the others and which shared the interests of a substantial portion of the citizenry, which was enough to garner them six seats in the regional assembly.

In short, political party brands are best established by creating real relationships with voters through broad-based civic activities the party undertakes to better society as they think best. This builds positive brands and valuable "up-close-and-personal" relationships with voters and activists.

Name changes are irrelevant and a waste of time in this process. You can slap a new coat of paint on your Lada and tell your friends it's a Mercedes, but that is not going to keep it from breaking down on the highway and preventing you from getting where you need to go.

Building personal relationships with voters is also the key to successful electoral campaigns. This is why the decision to abandon the tactic of meeting with voters in courtyards is also puzzling and disconcerting.

Time and again across the globe it has been proven that person-to-person encounters are the most effective means of voter persuasion and mobilization. So, unless voter contact through courtyard meetings is being abandoned in favor of even more personal door-to-door tactics, the party leaders are making a grave error in walking away from this methodology.

Rest assured that Russia is not the exception to the rule that person-to-person voter contact is the best means of voter communication on the planet. In the face of this reality, the first stop should be not to do away with proven methods but to ask: How might we execute them better?

If these decisions are a sign of the direction the party is heading in leading up to next year's elections, it does not bode well for their success in State Duma or regional contests, or for that matter beyond those elections for any reasonably foreseeable timeframe.

In assets like Leonid Volkov, the Democratic Coalition — in which RPR-Parnas is the major player — has the good fortune of being able to count on the expertise of some of the brightest and most savvy political campaign technologists in the country for their success in elections. The least the party could do is give these talented experts something to work with by endeavoring to build something in the way of a viable and credible organization between elections.

Reid Nelson is a political campaign consultant, democracy development specialist and lawyer who served as the Russia country director for the National Democratic Institute for four years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.