It seems nobody has reacted more emotionally to the migration crisis in Europe than the Russian people and the small community of Russians who have themselves migrated to Europe. Those who predict that Europe will inevitably collapse under the flood of refugees from the Middle East and Africa seem to have logic on their side. Meanwhile, those who advocate an open door policy can only meekly argue that the world should be free from national barriers.

This, I think, is the main debate in the world today: either humanity must live in a world divided by fences or else all fences should be eliminated.

Television coverage from the Serbian and Hungarian borders and reports of thousands of migrants who try every night to pass through the railway tunnel under the English Channel to reach British territory really do resemble movie scenes of the zombie apocalypse. We see images of uncontrollable and growing throngs of people, surprised and alarmed European citizens and confused security personnel desperately trying to manage the situation.

Thousands of people pour across the border of the European Union every day. That means the reassuring announcement that the number of migrants does not exceed half a million was wrong and that the EU will soon have to revise that figure upward — probably more than once.

There is no reason to believe that the smugglers operating in the Mediterranean will soon face a drop in demand: quite the contrary, demand will only grow. The number of refugees will continue to increase daily, monthly and even yearly.

And of course, those masses of humanity will include not only the victims of military conflicts, but also their combatants. It is not always possible to differentiate a terrorist from an ordinary citizen at an airport terminal, much less when pulling passengers from a half-sunken ferry boat or when screening them at a refugee camp. It really is an enormous problem.

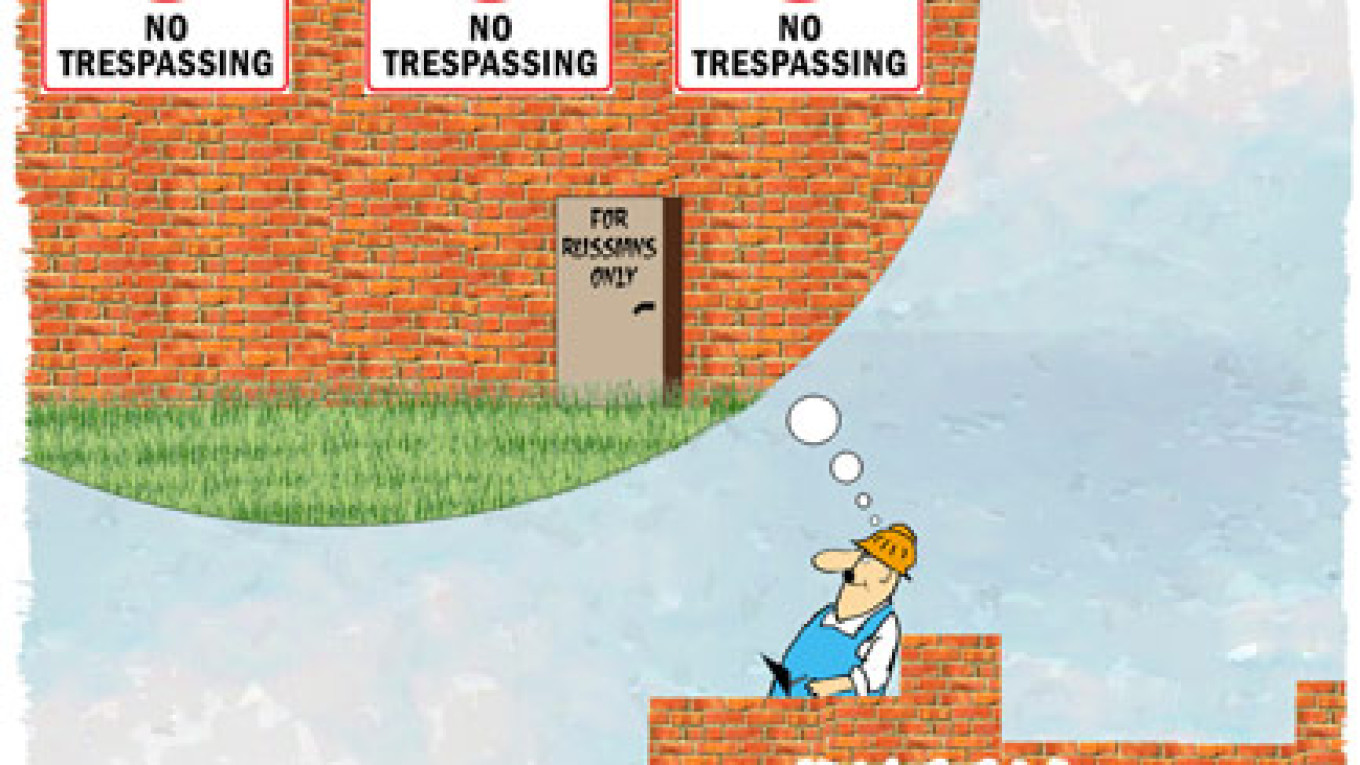

Until fairly recently, Europe still had walls that leaders could strengthen if necessary and gates that they could close and post with armed guards. This, indeed, is the question: In which type of world would you personally prefer to live? In a world of forbidding walls and guarded gates — or in a world where the gates stand wide open?

Many Russians clearly yearn for walls and closed gates. That is why they consider it pure madness, suicidal to open the gates to Europe to those who need help.

According to official statistics, Russia is second only to the United States as the country allowing in the most migrants. But do not be deceived by this honorable position in the ranking: The lion's share of migrants to Russia come from the former Soviet republics of Central Asia in search of jobs in a labor market that is shrinking due to the economic crisis.

Russia welcomes them only because they are willing to do the menial labor that nobody else wants. They are not welcome beyond this narrow social niche and nobody is inviting them to integrate into local communities. All of Russia's migration legislation is aimed at ensuring that they return to their homelands as quickly as possible. This is because, while Russian voters are not averse to exploiting migrant labor, they do not want those people as permanent neighbors.

And Russia has nothing to boast about regarding its attitude toward refugees. Prior to the conflict in Ukraine, Russia had granted asylum to only several hundred refugees in total.

On the one hand, there is little difference between the situation in Russia and that in Europe. Both have post-colonial peripheries that are in a state of partial economic, social and political collapse. And in both places, voters are not too thrilled with the appearance of a mosque down the street or the fact that, while riding on the subway, their native language is increasingly drowned out by Arabic or Tajik.

The difference is that Europeans seem to have realized that in the modern world freedom of movement is as inevitable as the sunrise and sunset. And that means that no matter how strict the rules of migration control are, the citizens of other countries will continue to arrive. They will come by plane, train, boat, raft or on foot.

Even the most remote and little-known corners of Europe in, say, the Czech Republic or Estonia, will not remain untouched. The world has become open simply as a result of technological changes: It is no longer possible to live as humanity once did 200, 100 or even 30 years ago.

This has two ramifications.

First, we must learn to live together. We must not merely tolerate neighbors who are different from us, but also respect them as equals. We must learn to see in diversity not just problems, but potential. At the same time, we must require that the newcomers comply with and respect the laws of the land along with everyone else.

Second, we must work toward bringing prosperity to every part of the planet because it is clear that the entire population of the Earth cannot live on the manicured lawns of Europe, North America and Australia — even if those regions were to suddenly eliminate all of their immigration restrictions.

Fences will not save anyone. That means humanity must remove those fences and ensure that manicured lawns appear everywhere. It must become possible to lead a good life everywhere, so that people would not feel compelled to flee their homelands with their children and belongings in search of sanctuary thousands of kilometers away on another continent.

Europe is trying now to make such a change, although clearly, it does not fully understand how to go about it. Russia is still trying to change the world in the opposite direction by closing its borders, dividing the continent into zones of influence and restricting freedom of movement.

In the world that the current Moscow regime is trying to build, an attempt to send a resume to Stockholm could land a person 14 years in a maximum security penal colony, as happened to engineer Gennady Kravtsov, who was convicted of treason a couple of days ago.

Paradoxically, few people are more adamantly opposed to accepting migrants in Europe than the Russians who have migrated there themselves. Unfortunately, they quickly forgot their own motivations. They cannot empathize with migrants who stand with their two children in their arms and their only suitcase in their hand and approach an immigration officer who has the power to grant them access to a world of manicured lawns, political stability and economic prosperity, while they leave behind a home blazing with the chaos of a crumbling state.

The way things are going, many who now advocate a policy of closed gates might soon find themselves in the same situation. At that moment they will suddenly call for an open world without walls and borders. Unfortunately, by that time the chance to create such a world might have been lost, thanks in part to their not so silent acquiescence.

Ivan Sukhov is a journalist who has covered conflicts in Russia and the CIS for the past 15 years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.