Mainstream discourse in Russia these days is overwhelmingly dominated by Ukraine. Ukraine this. Ukraine that. Look, a Russian rock star waved a Ukrainian flag on stage — let's burn her at the stake or at least strip her of her citizenship.

Ukrainian politicians, even boring, non-nationalist ones, are spoken of in tones of horror and disgust usually reserved for pedophiles and people who post animal abuse videos on the Internet.

Almost every Russian seems to have a story about how they have a wonderful Ukrainian friend/ex-classmate/third cousin on their dad's side whom they sadly can't talk to anymore, because — and here a dramatic pause is usually warranted — "they're all crazy over there now."

That's just what's happening on the surface, of course.

Even the sincerest supporter of Russia's loud denials of military involvement in Ukraine's east will probably agree that vast Russian intelligence resources have been engaged by the Ukraine crisis.

Spies, strategists, public thinkers and private advisers — how many useful people on the Russian side are currently devoting vast amounts of energy to Ukraine? The number is disturbing to consider due to the possibility that they're all wasting their time on the wrong problem.

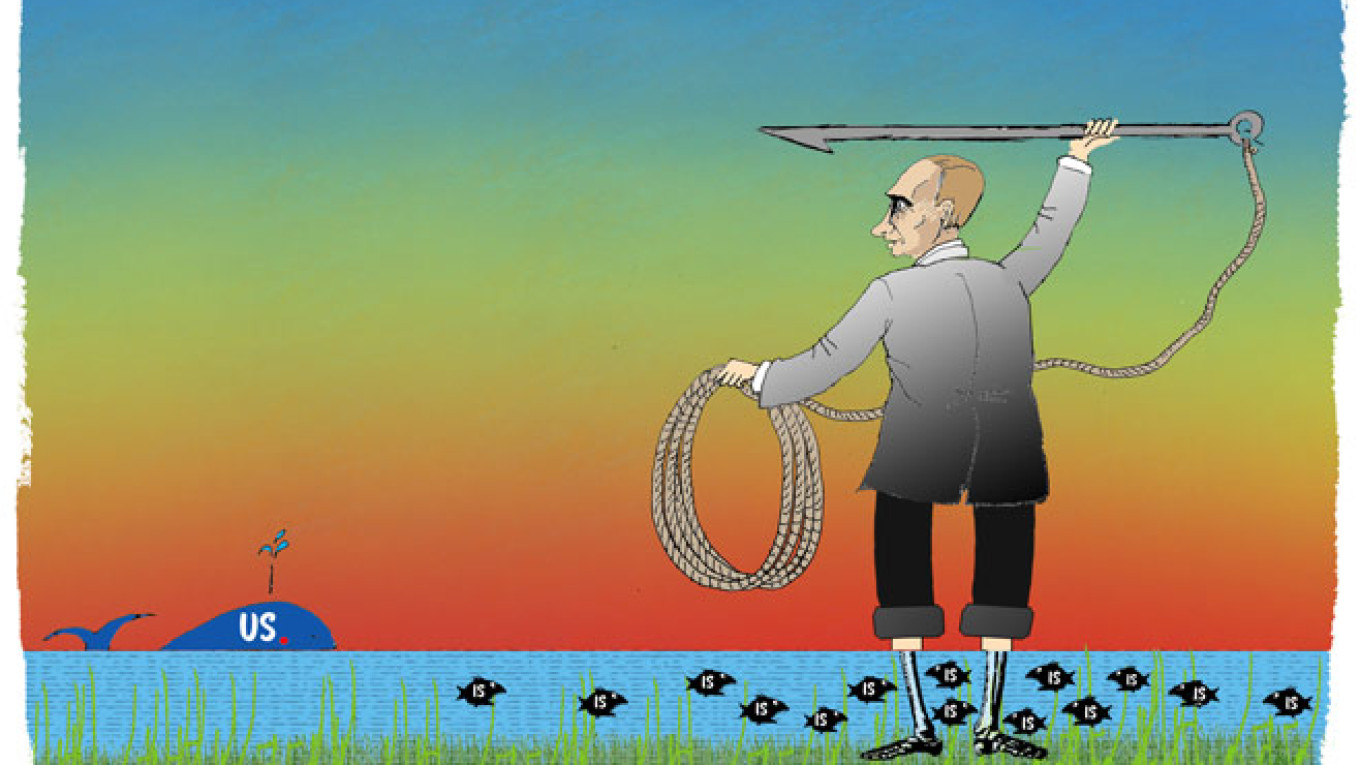

The real problem is the Islamic State.

Now, I realize that it's become fashionable to point out that the threat of the IS is "overstated." The IS is so fond of gory spectacle that a lot of people take a glance in their direction and assume that they're just compensating for military weaknesses — forgetting what a powerful tool violent propaganda in itself can be.

A sizable social media presence also makes the IS threat seem unbelievable at times. We're used to thinking of Islamic extremists as mysterious beings hiding in caves — not as people who get constantly retweeted into our feeds.

Perhaps so-called "Bloody Friday" on June 26, which saw deadly IS attacks take place in France, Tunisia and Kuwait can serve as a reminder that a terrorist who uses Twitter hashtags is still a terrorist.

Meanwhile, some countries are more vulnerable to the IS than others. Terror cells are scary enough — but Russia, for example, has its own political and geographic realities to think about. The North Caucasus region, already home to a number of extremists, is Russia's soft underbelly, a place where Moscow's influence has regularly been in flux.

The news that former al-Qaida militants in the North Caucasus have pledged allegiance to the IS was greeted with the usual complacency in Russia. "Oh, there's another message from crazy people pledging to slaughter us all — must be Tuesday," the weary nation says before switching the channel.

Yet it was exactly complacency over the IS that allowed the group so many unexpected military victories. And the North Caucasus, used to a steady diet of violence, is a fertile breeding ground for exactly the kind of apocalyptic message the IS brings.

That's besides reports that Muslims from Central Asia are radicalizing at alarming rates. There are millions of Central Asian migrants in Russia. Overall, they are an underpaid, exploited and alienated group. These are exactly the people the IS preys on by offering them a twisted kind of glory, as opposed to a life spent working thankless jobs for miniscule wages.

Since the annexation of Crimea and the onset of sanctions, both Russian foreign and domestic policy have been infused with a sense of exaggerated bravado and pointed anti-Western rhetoric.

In this atmosphere, Ukraine is the ideal "proxy enemy" — easy to demonize, but not nearly as imposing as the U.S., which is, polls show, considered to be the "ultimate enemy."

Russia can't really hurt the U.S., but in using Ukraine as a whipping boy it can hurt U.S. interests. It's also a great short-term tool for mobilizing society against an outside threat.

Admitting that Russia now shares with the West a particularly prolific and ruthless enemy — the IS, its sympathizers, and potential recruits — is an uncomfortable task. A common ground doesn't fit with the anti-Western narrative as neatly.

It also means toning down the bravado as far as Russia is concerned, which would go against the image of mighty Moscow, first rescuing Crimea from its Ukrainian captors and now ready to take on the world.

Russians can certainly point the finger at destructive U.S. misadventures in the Middle East as having given rise to the IS in the first place, but that can't and won't make the IS go away.

Titanic metaphors are appropriate here. Thomas Hardy was criticizing general human vanity when he wrote "And as the smart ship grew / In stature, grace, and hue, / In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too" — but these lines are just as appropriate for geopolitics.

So Russia puffs its chest out in the direction of Ukraine while the extremist cancer continues to grow — and where it could all end up is getting scary to contemplate.

Natalia Antonova is an American playwright and journalist.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.