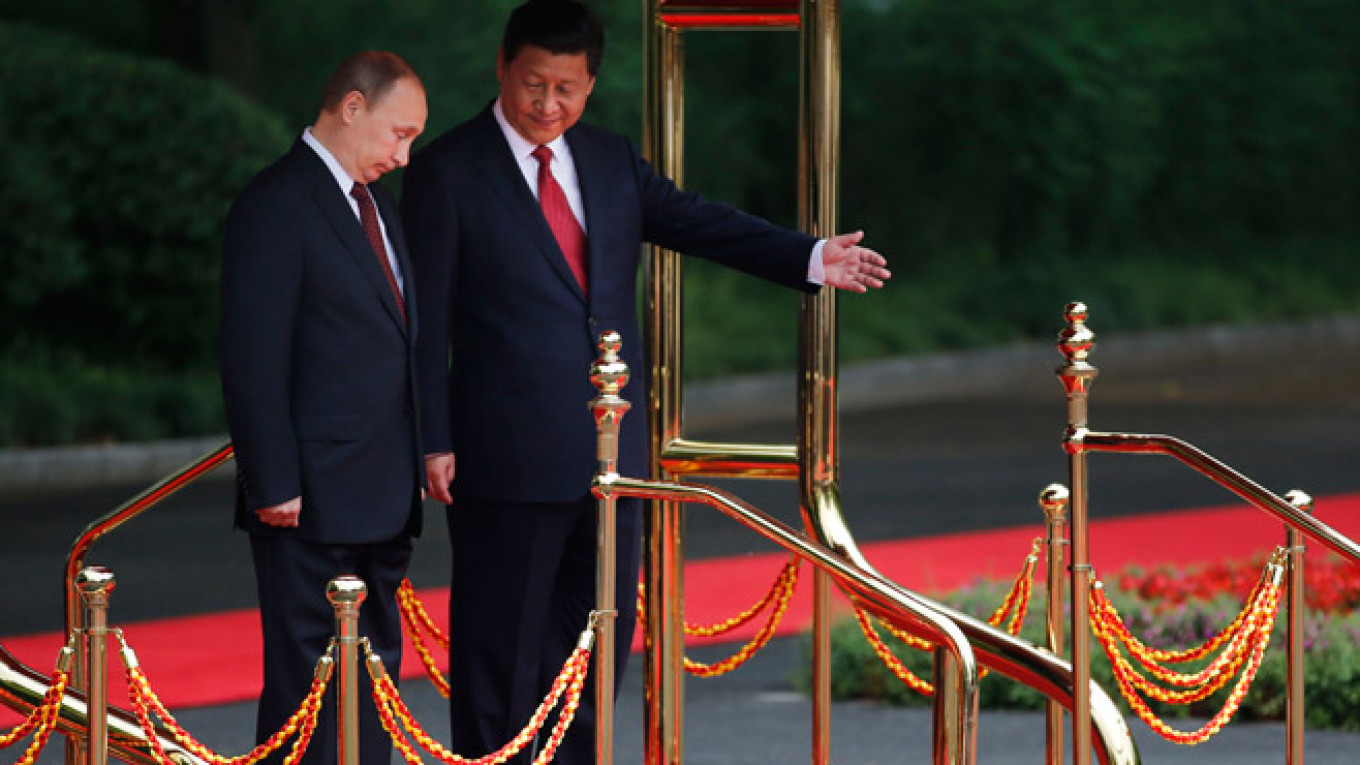

As Ukraine's political crisis poisons Russia's relationship with the West, Moscow is increasingly talking of China as a possible replacement for the European Union as Russia's key economic ally.

Such a pivot would mean Russia exchanging a partnership with the world's most economically developed region for closer ties with another developing nation. How will that shift transform the Russian economy?

Analysts interviewed by the Moscow Times said China can become a good-enough, if imperfect, replacement for the EU in most sectors of Russia's economy, including petroleum exports, technology and investment.

But an alliance with a developing nation would only solidify the economic status quo, they warned, doing nothing for Russia's chances of moving beyond a commodity economy.

Also, embracing China as its sole economic ally risks giving Beijing de facto control of the Russian economy — though that can be avoided if Moscow remembers to diversify its economic ties.

First Steps

And diversification seems to have been low on Russia's priority list in recent years, said Vasily Kashin of the Moscow-based Institute of Far Eastern Studies: Currently, Russia's trade relationship is unhealthily skewed toward Europe.

"We are just a raw materials supplier for a single market now," Kashin said. "So we can at least make it more than one market."

Russian exports to the EU stood at $238 billion, significantly above the imports, worth a mere $134 billion, according to the Federal Customs Service. Exports to China were at $35 billion over the same period, compared to $53 billion in imports.

Moscow has spent years mulling an eastward move, which can only be done through oil and gas, the linchpin of the Russian economy and the main reason to embrace Russia both for Brussels and for Beijing.

A breakthrough came Wednesday, when China signed a long-delayed 30-year deal worth $400 billion to buy Russian gas. The final price was not made public, but is estimated at $350 per 1,000 cubic meters — at the lower end of the price range Russia gets from European buyers.

The EU has long declared that it wants to cut dependence on energy exports from Russia. The issue has snapped into focus thanks to the crisis in Russia-West relations caused by the standoff in Ukraine, where Brussels and Moscow back opposing sides in a tense and occasionally bloody standoff teetering on the brink of civil war.

However, changing the direction of gas exports would take several years — most Russian pipelines are westward-bound.

Natalya Orlova, chief economist at Alfa Bank, sees benefits for both sides in Russia's reorientation east — Europe would diversify its energy imports, she said, while Russia could reduce the dependence of its economy on political conflicts like the one unfolding over Ukraine.

Luring In Chinese Money

European funds accounted for 75 percent of all direct foreign investment in Russia as of 2012, the latest year for which the Russian Mission to the EU has released figures. Russian official statistics put total direct foreign investment for that year at $18.6 billion.

European businesses have so far been keen to invest in Russia because it was outpacing the EU on growth, Orlova said. European funds have flowed into sectors ranging from energy to construction, IT, retail and manufacturing.

But whether China is interested in the Russian market beyond oil and gas is open to question.

China trounces Russia on economic growth, achieving 7.7 percent last year as against Russia's 1.3 percent. This means that Chinese investors, unlike European ones, will get a better return on their capital if they invest it at home, Orlova said.

"Chinese investment in Russia has been a trifle compared to investment from the rest of the world," agreed Konstantin Styrin, a professor of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. "We have nothing to offer [the Chinese] but oil."

But Kashin pointed out that the Chinese government is still encouraging businesses to invest abroad, which means at least some of the money will likely trickle down to Russia. China is chiefly interested in infrastructure and trade, but would invest in major industrial projects in Russia if they are well pitched and backed by the state — which basically leaves the ball in Moscow's court, he added.

Copying From Copycats

What Russia gets from Europe is technology: High-tech products and industrial equipment constituted 47 percent of imports inbound from the EU in 2013, according to Europe's statistics service, Eurostat. In contrast, 77 percent of Russian exports to the EU are oil and gas.

China, a developing nation, is no match for Europe when it comes to innovation, Styrin said.

But technology can still be had from China, which, while not a trailblazer in this field, is good at adopting advances made elsewhere and is not picky about sharing it, according to Kashin, who added: "It is not state-of-the-art, but it is good enough for us."

Besides, he said, many products imported by Russian companies from Europe are already Chinese-made — they are purchased in the West simply because the market is more familiar to Russians, where more businessmen read English than Chinese.

Alone With the Celestial Empire

The expert consensus was that Russia's main risk is over-reliance on China at the expense of other potential partners — China will have no qualms exploiting an over-exposed Russia if it can.

"China gets a very strong negotiating position" if Russia cuts ties to Europe, Orlova stated. Styrin was less equivocal, speaking about the risk of Russia becoming "hostage to buyer's market."

But Styrin also said the talk about severing ties with Europe is likely just a smokescreen for geopolitical bargaining over Ukraine and not a serious strategy.

And if Russia manages to strengthen its link to China while keeping other economic partners it would not bring about any structural change to the economy, but would actually be a long-awaited boost to development, Kashin said.

"If that happens, you could say this Ukrainian nightmare had some unexpected benefit, prompting an overdue move for which we have long lacked the political will," he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.