Synthetic marijuana, commonly sold under the genericized trademark Spice, offers a high that may be hundreds of times more intense than that of the drug it's designed to mimic — and it may kill you. But, most likely, it's legal.

Such newly synthesized designer drugs, whose absence from the federal blacklist makes them legal, can be bought online and shipped to Moscow. One such supplier, based in Shanghai, offers "fast delivery to Russia and Ukraine," "one to three days safe way to Moscow."

Russia has strict laws forbidding the promotion of drug use, and The Moscow Times was advised not to publish any names of websites selling synthetic marijuana.

According to Russian legislation, "analogues" of controlled substances should be treated as the very drugs they are emulating, but prosecution based on such similarity is difficult, said lawyer Sergei Klimenko of Khrenov & Partners. "The relatively few convictions regarding analogues testifies to this," he said by phone.

On Jan. 31, the Federal Drug Control Service announced that it had conducted a sweep of synthetic marijuana dealers, shutting down 55 points of sale, seizing 3,000 packets and detaining 30 people. But those suspects were soon released because their dope's active ingredient hadn't been banned, an agency spokesman said last week.

Federal Drug Control Service head Viktor Ivanov said after the raid that a compound found in most of the confiscated packets was "quinolin-8-yl 1-pentyl-1H-indole-3-carboxylate," a name he said symbolized the near-endless potential of synthesizing new compounds to circumvent anti-drug laws.

"Synthesis is unlimited. It enables extremely cheap and exclusively concentrated narcotics to be produced," he told a news conference. "The narcomafia is able practically every week to invent new forms of drugs and put them on the market."

The compound with the long name that Ivanov cited is sold as "PB-22" on the Shanghai-based supplier's website. The advertised purity is 99.5 percent, and "it's new and legal in Russia," the site notes.

"We are experiencing an especially large influx from Southeast Asia — Thailand, Burma, China," Ivanov told the conference. "We have confiscated about 2.5 million such shipments by mail." While in 2010 authorities seized no more than 60 kilograms of such drugs, "a year later officers confiscated more than 160 kilograms," he said.

But with the legal loophole, Russian authorities may be obliged to return such parcels if seized. At the news conference, Ivanov admitted that many of the suspects released after the raid were demanding their confiscated drugs back. "By law, we are obligated to return all of it," he said.

Ivanov said the Russian authorities had been aware of the drug known as PB-22 for only a month before the sweep. With new compounds popping up every few weeks, Ivanov suggested that one way to deal with the influx would be to more broadly engage the Federal Consumer Protection Service and prosecute for selling uncertified products.

"Spice is a genericized trademark. There are hundreds of these products, without trademarks, without quality certifications. There is no liability, criminal or administrative, for this type of quote-unquote 'product,'" he said.

Furthermore, Ivanov added, the drug control service is seeking a government mandate for broader jurisdiction over analogue drugs to crack down on newly synthesized compounds as they spring up.

"Already a while ago, Europe and the U.S. gave their law enforcement agencies the authority to halt, for up to a year and a half, the unconstrained civilian circulation of newly appearing drugs that have narcotic affects," he said, adding that such a mandate in Russia was possible within the next few years.

According to the Russian Criminal Code, possession of six grams of marijuana can mean a 40,000 ruble ($1,300) fine and up to three years in prison; 100 grams can mean a 500,000 ruble ($16,000) fine and up to 10 years. However, for the now-banned synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018, a one-hundredth of a gram can land the bearer up to three years behind bars; five one-hundredths can mean 10 years.

On Shanghai-based supplier's website, the minimum order size for the currently legal PB-22 is "one kilogram." But it was not immediately clear whether a license was required to purchase the compound, sold as a "research chemical." The site's phone number had been disconnected and an e-mail to the business had not been answered by Tuesday evening.

While deaths from overdose are extremely rare, synthetic marijuana has been attributed to kidney failure and acute coronary syndrome, a Federal Drug Control Service spokesman said Monday. "The drug affects all the vital organs: the brain, the kidneys, the liver," he warned.

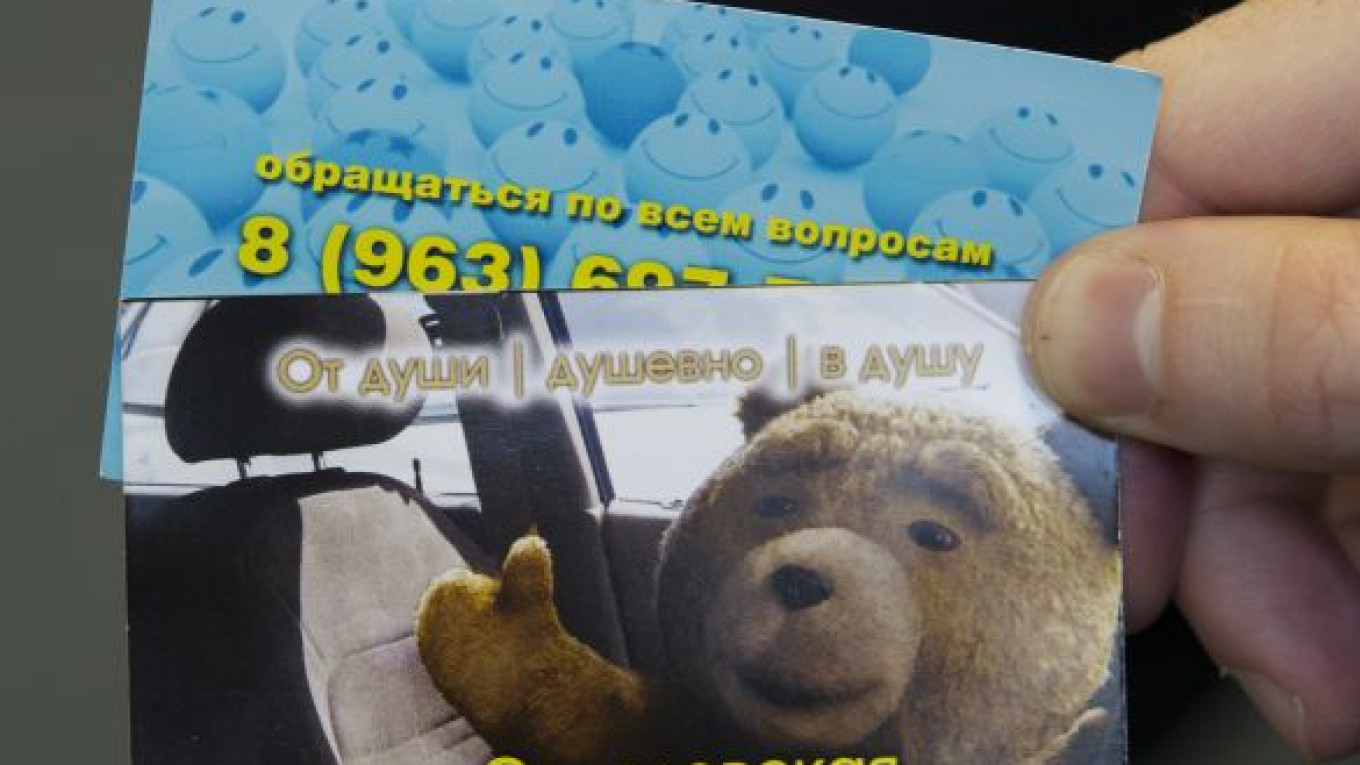

But while Spice dealers may still be legally allowed to ply their trade, this year's crackdown has had a noticeable effect on street peddling. In December people handing out flyers advertising smoking blends were nearly ubiquitous outside Moscow's metro stations, while by late February they had all but disappeared.

Perhaps they've been scared off, at least in part, by an offshoot of the pro-Kremlin Young Russia movement and its brigades of students turned vigilantes. Under the aegis of the so-called Youth Anti-Narcotics Task Force, masked men armed with hatchets and red paint roam Moscow's streets in search of drug dealers.

More than 50 college students conducted raids late last year, the group said. They approached dealers, beat them up and sprayed them with paint intended to remain on their skin for weeks.

"If an average person goes and sees a man who has unwashed red paint on his face, he immediately realizes what kind of person he is. Likewise, the police will be suspicious and stop, detain and search these traffickers," leader Alexei Grunichev said at the time on FM-City radio.

The group says these methods are more effective than police intervention.

On Feb. 12, news site Lenta.ru released a of one such raid, involving at least nine men, many in surgical masks, smashing the windshield of a suspected dealer's car, then striking him repeatedly, including with the butt of a hatchet, and spraying red paint on his already bloody face.

Contact the authors at newsreporter@imedia.ru

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.