The Bolshoi Theater closed its 2013-2014 season of ballet earlier this month with a brand-new work based on William Shakespeare's comedy "The Taming of the Shrew," in a staging by Jean-Christophe Maillot, director of Monaco's Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo and one of the world's most sought-after choreographers.

During his two decades as head of the Monte Carlo troupe, Maillot had previously refused all offers to create a new ballet for any other company. But the persuasive powers of the Bolshoi, principally in the person of its ballet artistic director, Sergei Filin, finally caused him to make an exception.

In an interview published in the Bolshoi's program book, Maillot added another reason for his change of heart. "No matter how long you have been working with your own company," he said, "when you are over 50 … you realize that there is less ahead than there is behind. It makes you regret not being more adventurous. Working with a new, unfamiliar company was a challenge I needed."

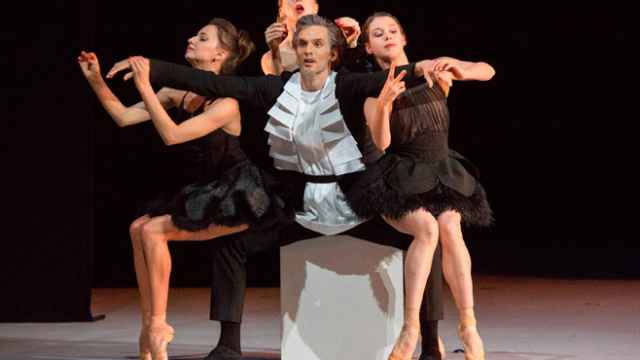

Maillot met the challenge superbly, creating for the Bolshoi some 90 minutes or so of nonstop, often breathtaking dance unlike any other to be seen on the theater's stages.

Maillot's brief excursion through what is probably the most erotic and "politically incorrect" of Shakespeare's plays reduces its complicated plot to focus mainly on the central characters: the ill-tempered, aggressive Katherina — the shrew of the title — who frightens away all potential husbands; her sister, the lovely and docile Bianca, who, according to tradition, must wait for a husband until the elder Katherina is safely married; Petruchio, a young man from Verona, who, in the words of his song from Cole Porter's Broadway musical version of the play, "Kiss Me, Kate," has "come to wive it wealthily in Padua" and, intent on obtaining Katherina's substantial dowry, shamelessly subdues her; and Lucentio, a rich, idle and none-too-bright young man who eventually gains Bianca's hand in marriage.

For a score to the ballet, Maillot turned to Dmitry Shostakovich, though not, with a few exceptions, to the profound Shostakovich with whom audiences are mostly familiar these days, but to the lighthearted tunes that the composer created for films and for his musical comedy "Moscow, Cheryomushki."

The 25 pieces were neatly woven together as a coherent score and given a delightful performance under the baton of the Moscow Conservatory's indefatigable champion of modern and contemporary music, Igor Dronov.

Maillot's choreography is firmly based on classical tradition and dance vocabulary. To that he adds the bits of quirky movement and the strong element of fantasy that are hallmarks of his work with Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo.

The show features lighthearted songs Shostakovich wrote for a comedy.

Decor for the production was created by Maillot's longtime collaborator Ernest Pignon-Ernest. The simple, but highly effective set consists mainly of a huge staircase, seen first in the form of an arc, and then divided into two equal parts, plus a series of tall columns. Combined with the extraordinary lighting scheme of Dominique Drillot — among the most sophisticated I have ever seen in any theater — these serve perfectly to frame the action.

The costumes, an eclectic and cheerful mix, in styles that seemed to draw much inspiration from Hollywood of the 1930s, are the work of the choreographer's son, Augustin Maillot, a protegee of designer Karl Lagerfeld.

The two casts fielded by the Bolshoi for "Taming of the Shrew" managed to bring to it two remarkably different interpretations, both of which seemed equally persuasive.

The great surprise and joy among the first cast was the Katherina of Yekaterina Krysanova, who added to her superb technical proficiency an openness, freedom and eroticism the likes of which I have never before witnessed in her dancing. Her Petruchio, the handsome and enormously talented Vladislav Lantratov, almost as effectively broke free from the constraints of classical ballet and threw himself wholeheartedly into the process of subjugating his intended bride.

The second cast's Katherina, Maria Aleksandrova, seemed even more aggressive and ill-tempered than Krysanova in the earlier scenes and a shade more lyrical when finally conquered. Denis Savin's Petruchio was much less a monster than Lantratov's, but proved convincing nevertheless.

As Bianca and Lucentio, the girlish Anastasia Stashkevich and boyish Artyom Ovcharenko of the second cast played in sharp contrast to the suave Olga Smirnova and somewhat befuddled Semyon Chudin of the first cast. All four danced splendidly.

Every one of the other eight soloists in each cast could be singled out for special praise, as could each group of a dozen lively maids and male servants that served as a sort of mini-corps de ballet.

"The Taming of the Shrew" (Ukroshcheniye Stroptivoi) next plays on Oct. 3 and 4 at 7 p.m., Oct. 4 at noon and Oct. 5 at 6 p.m. at the New Stage of the Bolshoi Theater, located at 1 Teatralnaya Ploshchad. Metro Teatralnaya. Tel. (495) 455-5555. www.bolshoi.ru.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.